15 February 1961, 09:05 UTC: This Boeing 707-329 airliner, registration OO-SJB, under the command of Captain Ludovic Marie Antoine Lambrechts and Captain Jean Roy, was enroute from Idlewild Airport, New York (IDL) to Brussels-Zaventem Airport (BRU) as SABENA Flight SN548, when three miles (4.8 kilometers) short of the runway at an altitude of 900 feet (274 meters), it pulled up, retracted its landing gear and accelerated.

The airliner made three 360° circles, with the angle of bank steadily increasing to 90°. The 707’s wings then leveled, followed by an abrupt pitch up. OO-SJB spiraled into a nose-down dive and crashed into an open field 1.9 miles (3 kilometers) northeast of Brussels and all 61 passengers and 11 crew members and 1 person on the ground were killed, including the entire U.S. Figure Skating Association team, their families, coaches, judges and officials.

The cause of the crash was never determined but is suspected to be a mechanical failure in the flight control system:

Probable Cause

Having carried out all possible reasonable investigations, the Commission concluded that the cause of the accident had to be looked for in the material failure of the flying controls.

However, while it was possible to advance certain hypotheses regarding the possible causes, they could not be considered entirely satisfactory. Only the material failure of two systems could lead to a complete explanation, but left the way open to an arbitrary choice because there was not sufficient evidence to corroborate it.

—ICAO Circular 69-AN/61, Page 55, Column 2

The Federal Aviation Administration’s comments were included in the accident report:

“Of the several hypotheses evolving from findings in the accident report, we believe the most plausible to be that concerned with a malfunction of the stabilizer adjusting mechanism permitting the stabilizer to run to the 10.5-degree nose-up position. If such a malfunction occurred and the split flaps and spoilers procedure (inboard spoilers and outboard flaps extended) not employed, the only means to prevent the aircraft from pitching up into a stall would be to apply full forward column and enter a turn in either direction.”

“It is apparent from the recorded impact positions that the split flaps and spoilers technique was not used. The wing flaps were found in the up position and had the inboard spoilers been extended both would have been up at impact and the speed brake handle would not have been in the neutral position as found.”

—ICAO Circular 69-AN/61, Page 56, Column 2

Societé Anonyme Belge d’Exploitation de la Navigation Aérienne (SABENA) was the national airline of Belgium. It was based at Brussels and operated from 1923 to 2001.

SABENA Flight SN548 was a Boeing 707-329 Intercontinental, OO-SJB, Boeing serial number 17624. It made its first test flight 13 December 1959 at Renton, Washington, and was delivered to SABENA in January 1960. At the time of the accident, it had just 3,038 total flight hours (TTAF). The airplane had undergone a Type II overhaul just 37 hours before the crash. ¹

The Boeing 707 was a jet airliner which had been developed from the Model 367–80 prototype, the “Dash Eighty.” It was a four-engine jet transport with swept wings and tail surfaces. The leading edge of the wings were swept at a 35° angle. The airliner had a flight crew of four: pilot, co-pilot, navigator and flight engineer.

The 707-329 Intercontinental is 152 feet, 11 inches (46.611 meters) long with a wing span of 145 feet, 9 inches (44.425 meters). The top of the vertical fin stands 42 feet, 5 inches (12.928 meters) high. The wing is considerably different than on the original 707-120 series, with increased length, different flaps and spoilers, and the engines are mounted further outboard. The vertical fin is taller, the horizontal tail plane has increased span, and there is a ventral fin for improved longitudinal stability. The 707 pre-dated the ”wide-body” airliners, having a fuselage width of 12 feet, 4 inches (3.759 meters).

The the 707-320 International-series had an operating empty weight of 142,600 pounds (64,682 kilograms). Its maximum take off weight (MTOW) was 312,000 pounds (141,521 kilograms). When OO-SJB departed New York, its total weight was 119,500 kilograms (263,452 pounds), well below MTOW. It carried 50,000 kilograms (110,231 pounds) of JP-1 fuel.

OO-SJB was powered by four Pratt & Whitney Turbo Wasp JT4A engines. These were two-spool, axial-flow turbojet engine with a 15-stage compressor (8 low-, 7 high-pressure stages) and 3-stage turbine (1 high- and 2 low-pressure stages). The –12 was rated at 14,900 pounds of thrust (66.279 kilonewtons), maximum continuous power, and 17,500 pounds of thrust (77.844 kilonewtons) at 9,355 r.p.m. (N₂) for takeoff. The engine was 12 feet, 0.1 inches (3.660 meters) long, 3 feet, 6.5 inches (1.080 meters) in diameter, and weighed 4,895 pounds (2,220 kilograms).

The 707-329 had a maximum operating speed (MMO) of 0.887 Mach above 25,000 feet (7,620 meters). At 24,900 feet (7,590 meters), its maximum indicated airspeed (VMO) was 378 knots (435 miles per hour/700 kilometers per hour). At MTOW, the 707-329 required 10,840 feet (3,304 meters) of runway for takeoff. It had a range of 4,298 miles (6,917 kilometers).

The Boeing 707 was in production from 1958 to 1979. 1,010 were built.

According to the accident investigation report, following this overhaul, which took place from 11 January to 9 February 1961,

1) The pilot noted that during the first test flight on 9 February 1962 the trim button had to be pushed harder than normal. A second test flight was made to confirm the fault, after which the pilot noted “abnormal response of the stabilizer particularly after trimming nose down; slight nose up impulses give no result.”

2) The second incident was observed during the same flight. The pilot noted: “At the beginning of the flight there was a strong tendency of the aircraft to roll to the right. In level flight, the two left wing spoilers are 1 inch out.

“After descent, speed brakes out, at the moment of their retraction there was a marked roll to the right – it did not recur afterwards.

“At the end of the flight, the tendency to roll to the right was considerably diminished.”

—ICAO Circular 69-AN/61, Page 44, Column 2

In response to the stabilzer trim concern, maintenance replaced the stabilizer trim motor. It functioned normally during ground tests. As to the roll issue, an inspection following the flight did not reveal anything abnormal.

© 2021, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

15 February 1946: First flight of Douglas XC-112A (s/n 36326) 45-873.

15 February 1946: First flight of Douglas XC-112A (s/n 36326) 45-873.

In 1944, the U.S. Army Air Corps had requested a faster, higher-flying variant of the Douglas C-54E Skymaster, with a pressurized cabin. Douglas Aircraft Company developed the XC-112A in response. It was completed 11 February 1946 and made its first flight 4 days later. With the end of World War II, military requirements were scaled back and no orders for the type were placed.

Douglas saw a need for a new post-war civil airliner to compete with the Lockheed L-049 Constellation. Based on the XC-112A, the prototype Douglas DC-6 was built and made its first flight four months later, 29 June 1946.

The Air Force ordered the twenty-sixth production Douglas DC-6 as a presidential transport, designated VC-118, The Independence. Beginning in 1951, the Air Force ordered a variant of the DC-6A as a the C-118A Liftmaster military transport and MC-118A medical transport. The U.S. Navy ordered it as the R6D-1.

The Douglas DC-6 was flown by a pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer and a navigator on longer flights. It was designed to carry between 48 and 68 passengers, depending on variant.

The DC-6 was 100 feet, 7 inches (30.658 meters) long with a wingspan of 117 feet, 6 inches (35.814 meters) and overall height of 28 feet, 5 inches (8.612 meters). The aircraft had an empty weight of 55,567 pounds (25,205 kilograms) and maximum takeoff weight of 97,200 pounds (44,090 kilograms).

The initial production DC-6 was powered by four 2,804.4-cubic-inch-displacement (45.956 liter), air-cooled, supercharged Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp CA15 two-row, 18 cylinder radial engines with a compression ratio of 6.75:1. The CA15 had a Normal Power rating of 1,800 h.p. at 2,600 r.p.m. at 6,000 feet (1,829 meters), 1,600 horsepower at 16,000 feet (4,877 meters), and 2,400 h.p. at 2,800 r.p.m with water injection for take off. The engines drove three-bladed Hamilton Standard Hydromatic 43E60 constant-speed propellers with a 15 foot, 2 inch (4.623 meter) diameter through a 0.450:1 gear reduction. The Double Wasp CA15 was 6 feet, 4.39 inches (1.940 meters) long, 4 feet, 4.80 inches (1.341 meters) in diameter, and weighed 2,330 pounds (1,057 kilograms).

The initial production DC-6 was powered by four 2,804.4-cubic-inch-displacement (45.956 liter), air-cooled, supercharged Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp CA15 two-row, 18 cylinder radial engines with a compression ratio of 6.75:1. The CA15 had a Normal Power rating of 1,800 h.p. at 2,600 r.p.m. at 6,000 feet (1,829 meters), 1,600 horsepower at 16,000 feet (4,877 meters), and 2,400 h.p. at 2,800 r.p.m with water injection for take off. The engines drove three-bladed Hamilton Standard Hydromatic 43E60 constant-speed propellers with a 15 foot, 2 inch (4.623 meter) diameter through a 0.450:1 gear reduction. The Double Wasp CA15 was 6 feet, 4.39 inches (1.940 meters) long, 4 feet, 4.80 inches (1.341 meters) in diameter, and weighed 2,330 pounds (1,057 kilograms).

The Douglas DC-6 had a cruise speed of 311 miles per hour (501 kilometers per hour) and range of 4,584 miles (7,377 kilometers).

XC-112A 45-873 was redesignated YC-112A and was retained by the Air Force before being transferred to the Civil Aeronautics Administration at Oklahoma City, where it was used as a ground trainer. 36326 was sold at auction as surplus equipment, and was purchased by Conner Airlines, Inc. Miami, Florida and received its first civil registration, N6166G, 1 August 1956. The YC-112A was certified in the transport category, 20 August 1956.

Conner Airlines sold 36326 to Compañia Ecuatoriana de Aviación (CEA), an Ecuadorian airline. Registered HC-ADJ, Ecuatoriana operated 36326 for several years.

It was next re-registered N6166G, 1 August 1962, owned by ASA International. A few months later, 1 May 1963, 36326 was registered to Trabajeros Aereos del Sahara SA (TASSA) a Spanish charter company specializing in the support of oil drilling operations in the Sahara, registered EC-AUC.

In 1965, with a private owner, 36326 was once again re-registered N6166G. Just two weeks after that, 1 June 1965, 36326 was registered to TransAir Canada as CF-TAX.

Two years later, 13 June 1967, Mercer Airlines bought 36326. This time the airplane was registered N901MA. Mercer was a charter company which also operated a Douglas C-47 and Douglas DC-4.

A Las Vegas, Nevada, hotel chartered Mercer Airlines to fly a group of passengers from Ontario International Airport (ONT), Ontario, California, to McCarran International Airport (LAS). On 8 February 1976, 36326, operating as Mercer Flight 901, was preparing to fly from Hollywood-Burbank Airport (BUR) where it was based, to ONT. The airliner had a flight crew of three: Captain James R. Seccombe, First Officer Jack R. Finger, Flight Engineer Arthur M. Bankers. There were two flight attendants in the passenger cabin, along with another Mercer employee.

Weather at BUR was reported as 1,000 feet (305 meters) scattered, 7,000 feet (2,134 meters) overcast, with visibility 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) in light rain and fog. The air temperature was 56 °F. (13.3 °C.), the wind was 180° at 4 knots (2 meters per second).

At 10:35 a.m. PST (18:35 UTC), Flight 901 was cleared for a rolling takeoff on Burbank’s Runway 15. While on takeoff roll, Flight Engineer Bankers observed a warning light for engine #3 (inboard, starboard wing). He called out a warning to the Captain, however, the takeoff continued.

Immediately after takeoff, a propeller blade on #3 failed. The intense vibration from the unbalanced propeller tore the #3 engine off of the airplane’s wing, and it fell on to the runway below.

The thrown blade passed through the lower fuselage, cut through hydraulic and pneumatic lines and electrical cables and then struck the #2 engine (inboard, port wing), further damaging the airplane’s electrical components and putting a large hole in that engine’s forward accessory drive case. The engine rapidly lost lubricating oil.

Flight 901 declared an emergency and requested to land on Runway 07, which was approved by the Burbank control tower, though they were informed that debris from the engine was on the runway at the intersection of 15/33 and 07/25. The airplane circled to the right to line up for Runway 07.

Just prior to touchdown, warning lights indicated that the propeller on the #2 engine had reversed. (In fact, it had not.) Captain Seccombe announced that they would only reverse #1 and #4 (the outboard engines, port and starboard wings) to slow 36326 after landing, and the airplane touched down very close to the approach end of the runway.

Because of the damage to the airplane’s systems, the outboard propellers would not reverse to slow the airplane and the service and emergency brakes also had failed. N901MA was in danger of running off the east end of the 6,055 foot (1,846 meters) runway, across the busy Hollywood Way and on into the city beyond.

The flight crew applied full power on the remaining three engines and again took off. The landing gear would not retract. The electrical systems failed. The #2 engine lost oil pressure and began to slow.

The DC-6 circled to the right again and headed toward Van Nuys Airport (VNY), 6.9 miles (11.1 kilometers) west of Hollywood-Burbank Airport. They informed Burbank tower that they would be landing on Van Nuys Runway 34L which was 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) long. Because of the emergency, the crew remained on Burbank’s radio frequency. The #2 engine then stopped but the propeller could not be feathered.

Van Nuys weather was reported as 600 feet (183 meters) scattered, 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) overcast, with visibility 10 miles (16.1 kilometers) in light rain, temperature 55 °F. (12.8 °C.). The airliner was flying in and out of the clouds and the crew was on instruments. [1045: “Special, 1,200 scattered, 10,000 feet overcast, visibility—10 miles, rainshowers, wind—130° at 4 kn, altimeter setting—29.93 in.”]

Because of the drag of the unfeathered engine #2 propeller and the extended landing gear, the Flight 901 was unable to maintain altitude with the two remaining engines. The airplane was not able to reach the runway at VNY.

A forced landing was made on a golf course just south of the airport. The airplane touched down about 1 mile south of the threshold of Runway 34L on the main landing gear and bounced three times. At 10:44:55, the nose then struck the foundation of a partially constructed building, crushing the cockpit. All three flight crew members were killed by the impact.

Both flight attendants were trapped under their damaged seats but were able to free themselves. They and the passenger were able to escape from the wreck with minor injuries.

Los Angeles City Fire Department firefighters attempted to rescue the crew by cutting into the fuselage. Even though the area around the airplane had been covered with fire-retardant foam, at about 20 minutes after the crash, sparks from the power saw ignited gasoline fumes. Fire erupted around the airplane. Ten firefighters were burned, three severely. N901MA was destroyed.

At the time of the accident, YC-112A 36326 was just three days short of the 30th anniversary of its completion at Douglas. It had flown a total of 10,280.4 hours. It was powered by three Pratt & Whitney R-2800-83 AMS, and one R-2800-CA18 Double Wasp engines. All four engines drove three-bladed Curtiss-Wright Type C632-S constant-speed propellers. The failed propeller had been overhauled then installed on N901MA 85 hours prior to the 8 February flight.

The National Transportation Safety Board investigated the accident. It was found that a fatigue fracture in the leading edge of the propeller blade had caused the failure. Though the propeller had recently been overhauled, it was discovered that the most recent procedures had not been followed. This required that the rubber deicing boots be stripped so that a magnetic inspection could be made of the blade’s entire surface. Because this had not been done, the crack in the hollow steel blade was not found.

© 2019, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

14 February 2012: Boeing YAL-1A Airborne Laser Test Bed, serial number 00-0001, departed Edwards AFB for the last time as it headed for The Boneyard at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Tucson, Arizona.

The Boeing YAL-1A was built from a 747-4G4F, a converted 747-400F freighter, serial number 30201, formerly operated by Japan Air Lines and registered JA402J. It carried two solid state lasers and a megawatt-class oxygen iodine directed energy weapon system (COIL).

On 3 February 2010, it destroyed a Terrier Black Brant two-stage sounding rocket in the boost phase as it was launched from San Nicolas Island, off the coast of Southern California.

![]() The 747-400 was a major development of the 747 series. It had many structural and electronics improvements over the earlier models, which had debuted 18 years earlier. New systems, such as a “glass cockpit”, flight management computers, and new engines allowed it to be flown with a crew of just two pilots, and the position of Flight Engineer became unnecessary.

The 747-400 was a major development of the 747 series. It had many structural and electronics improvements over the earlier models, which had debuted 18 years earlier. New systems, such as a “glass cockpit”, flight management computers, and new engines allowed it to be flown with a crew of just two pilots, and the position of Flight Engineer became unnecessary.

The most visible features of the –400 are its longer upper deck and the six-foot tall “winglets” at the end of each wing, which improve aerodynamic efficiency be limiting the formation of wing-tip vortices.

The Boeing 747-400F is the freighter version of the 747-400 airliner. It has a shorter upper deck, no passenger windows and the nose can swing upward to allow cargo pallets or containers to be loaded. It is 231 feet, 10 inches (70.663 meters) long with a wingspan of 211 feet, 5 inches (64.440 meters) and overall height of 63 feet, 8 inches (19.406 meters). Empty weight is 394,100 pounds (178,761 kilograms). Maximum takeoff weight (MTOW) is 875,000 pounds (396,893 kilograms).

The YAL-1A was powered by four General Electric CF6-80C2B5F turbofan engines, producing 62,100 pounds of thrust (276.235 kilonewtons), each. The CF6-80C2B5F is a two-spool, high-bypass-ratio turbofan engine. It has a single-stage fan section, 18-stage compressor (4 low- and 14 high-pressure stages) and 7-stage turbine section (2 high- and 5 low-pressure stages). The fan diameter is 7 feet, 9.0 inches (2.362 meters). The engine is 13 feet, 4.9 inches (4.087 meters) long with a maximum diameter of 8 feet, 10.0 inches (2.692 meters). It weighs 9,760 pounds (4,427 kilograms).

The YAL-1A was powered by four General Electric CF6-80C2B5F turbofan engines, producing 62,100 pounds of thrust (276.235 kilonewtons), each. The CF6-80C2B5F is a two-spool, high-bypass-ratio turbofan engine. It has a single-stage fan section, 18-stage compressor (4 low- and 14 high-pressure stages) and 7-stage turbine section (2 high- and 5 low-pressure stages). The fan diameter is 7 feet, 9.0 inches (2.362 meters). The engine is 13 feet, 4.9 inches (4.087 meters) long with a maximum diameter of 8 feet, 10.0 inches (2.692 meters). It weighs 9,760 pounds (4,427 kilograms).

It had a cruise speed of 0.84 Mach (555 miles per hour, 893 kilometers per hour) at 35,000 feet (10,668 meters) and maximum speed of 0.92 Mach (608 miles per hour, 978 kilometers hour). Maximum range at maximum payload weight is 7,260 nautical miles (13,446 kilometers).

© 2017, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

14 February 1991: An unusual incident occurred during Desert Storm, when Captains Tim Bennett and Dan Bakke, United States Air Force, flying the airplane in the above photograph, McDonnell Douglas F-15E-47-MC Strike Eagle, 89-0487, used a 2,000-pound (907.2 kilogram) GBU-10 Paveway II laser-guided bomb to “shoot down” an Iraqi Mil Mi-24 Hind attack helicopter. This airplane is still in service with the Air Force, and on 17 May 2024 logged its 15,000th flight hour.

Captain Bennett (Pilot) and Captain Bakke (Weapon Systems Officer) were leading a two-ship flight on a anti-Scud missile patrol, waiting for a target to be assigned by their Boeing E-3 AWACS controller. 89-0487 was armed with four laser-guided GBU-10 bombs and four AIM-9 Sidewinder heat-seeking air-to-air missiles. Their wingman was carrying twelve Mk. 82 500-pound (227 kilogram) bombs.

The AWACS controller called Bennett’s flight and told them that a Special Forces team on the ground searching for Scud launching sites had been located by Iraqi forces and was in need of help. They headed in from 50 miles (80.5 kilometers) away, descending though 12,000 feet (3,658 meters) of clouds as the went. They came out of the clouds at 2,500 feet (762 meters), 15–20 miles (24– 32 kilometers) from the Special Forces team.

With the Strike Eagle’s infrared targeting pod, they picked up five helicopters and identified them as enemy Mi-24s. It appeared that the helicopters were trying to drive the U.S. soldiers into a waiting Iraqi blocking force.

Their Strike Eagle was inbound at 600 knots (1,111 kilometers per hour) and both the FLIR (infrared) targeting pod and search radar were locked on to the Iraqi helicopters. Dan Bakke aimed the laser targeting designator at the lead helicopter preparing to drop a GBU-10 while Tim Bennett was getting a Sidewinder missile ready to fire. At four miles (6.44 kilometers) they released the GBU-10.

At this time, the enemy helicopter, which had been either on the ground or in a hover, began to accelerate and climb. The Eagle’s radar showed the helicopter’s ground speed at 100 knots. Bakke struggled to keep the laser designator on the fast-moving target. Bennett was about to fire the Sidewinder at the helicopter when the 2,000-pound (907.2 kilogram) bomb hit and detonated. The helicopter ceased to exist. The other four helicopters scattered.

Soon after, additional fighter bombers arrived to defend the U.S. Special Forces team. They were later extracted and were able to confirm the Strike Eagle’s kill.

The Strike Eagle was begun as a private venture by McDonnell Douglas. Designed to be operated by a pilot and a weapon system officer (WSO), the airplane can carry bombs, missiles and guns for a ground attack role, while maintaining its capability as an air superiority fighter. It’s airframe was a strengthened and its service life doubled to 16,000 flight hours. The Strike Eagle became an Air Force project in March 1981, and went into production as the F-15E. The first production model, 86-0183, made its first flight 11 December 1986.

The Strike Eagle was begun as a private venture by McDonnell Douglas. Designed to be operated by a pilot and a weapon system officer (WSO), the airplane can carry bombs, missiles and guns for a ground attack role, while maintaining its capability as an air superiority fighter. It’s airframe was a strengthened and its service life doubled to 16,000 flight hours. The Strike Eagle became an Air Force project in March 1981, and went into production as the F-15E. The first production model, 86-0183, made its first flight 11 December 1986.

The McDonnell Douglas F-15E Strike Eagle is a two-place twin-engine multi-role fighter. It is 63 feet, 9 inches (19.431 meters) long with a wingspan of 42 feet, 9¾ inches (13.049 meters) and height of 18 feet, 5½ inches (5.626 meters). It weighs 31,700 pounds (14,379 kilograms) empty and has a maximum takeoff weight of 81,000 pounds (36,741 kilograms).

The F-15E is powered by two Pratt and Whitney F100-PW-229 turbofan engines which produce 17,800 pounds of thrust (79.178 kilonewtons) each, or 29,100 pounds (129.443 kilonewtons) with afterburner.

The F-15E is powered by two Pratt and Whitney F100-PW-229 turbofan engines which produce 17,800 pounds of thrust (79.178 kilonewtons) each, or 29,100 pounds (129.443 kilonewtons) with afterburner.

The Strike Eagle has a maximum speed of Mach 2.54 (1,676 miles per hour, (2,697 kilometers per hour) at 40,000 feet (12,192 meters) and is capable of sustained speed at Mach 2.3 (1,520 miles per hour, 2,446 kilometers per hour). Its service ceiling is 60,000 feet (18,288 meters). The fighter-bomber has a combat radius of 790 miles (1,271 kilometers) and a maximum ferry range of 2,765 miles (4,450 kilometers).

Though optimized as a fighter-bomber, the F-15E Strike Eagle retains an air-to-air combat capability. The F-15E is armed with one 20mm M61A1 Vulcan 6-barrel rotary cannon with 512 rounds of ammunition, and can carry four AIM-9M Sidewinder heat-seeking missiles and four AIM-7M Sparrow radar-guided missiles, or a combination of Sidewinders, Sparrows and AIM-120 AMRAAM long range missiles. It can carry a maximum load of 24,500 pounds (11,113 kilograms) of bombs and missiles for ground attack.

The Mil Mi-24 (NATO reporting name “Hind”) is a large, heavily-armed attack helicopter that can also carry up to eight troops. It is flown by a pilot and a gunner.

The Mil Mi-24 (NATO reporting name “Hind”) is a large, heavily-armed attack helicopter that can also carry up to eight troops. It is flown by a pilot and a gunner.

It is 57 feet, 4 inches (17.475 meters) long and the five-bladed main rotor has a diameter of 56 feet, 7 inches (17.247 meters). The helicopter has an overall height of 21 feet, 3 inches (6.477 meters). The empty weight is 18,740 pounds (8,378 kilograms) and maximum takeoff weight is 26,500 pounds (12,020 kilograms).

![]() The helicopter is powered by two Isotov TV3-117 turboshaft engines which produce 2,200 horsepower, each. The Mil-24 has a maximum speed of 208 miles per hour (335 kilometers per hour) and a range of 280 miles (451 kilometers). Its service ceiling is 14,750 feet (4,496 meters).

The helicopter is powered by two Isotov TV3-117 turboshaft engines which produce 2,200 horsepower, each. The Mil-24 has a maximum speed of 208 miles per hour (335 kilometers per hour) and a range of 280 miles (451 kilometers). Its service ceiling is 14,750 feet (4,496 meters).

The helicopter is armed with a 12.7 mm Yakushev-Borzov Yak-B four-barreled Gatling gun with 1,470 rounds of ammunition; a twin-barrel GSh-30K 30 mm autocannon with 750 rounds; a twin-barrel GSh-23L 23 mm autocannon with 450 rounds. The Mi-24 can also carry a wide range of bombs, rockets and missiles.

The Mil Mi-24 first flew in 1969 and is still in production. More than 2,300 have been built and they have served the militaries of forty countries.

© 2019, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

14 February 1979: Flying her Grob G102 Astir CS glider from the Black Forest Gliderport, north of Colorado Springs, Colorado, Sabrina Patricia Jackintell soared to an altitude of 12,637 meters (41,460 feet) over Pikes Peak, setting a Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) World Record and Soaring Society of America National Record for Absolute Altitude.¹ This record still stands. The duration of this flight was 3 hours, 18 minutes.

14 February 1979: Flying her Grob G102 Astir CS glider from the Black Forest Gliderport, north of Colorado Springs, Colorado, Sabrina Patricia Jackintell soared to an altitude of 12,637 meters (41,460 feet) over Pikes Peak, setting a Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) World Record and Soaring Society of America National Record for Absolute Altitude.¹ This record still stands. The duration of this flight was 3 hours, 18 minutes.

Pike’s Peak is the highest mountain in the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The 14,115 foot (4,267 meters) summit is located 12 miles (19.3 kilometers) west of Colorado Springs.

![]() Sabrina Jackintell’s aircraft was a 1976 Grob G102 Astir CS glider (or sailplane), serial number 1171, FAA registration N75SW. The Astir CS is registered in the experimental category. It is approved for Day VFR Flight and may perform simple aerobatics: loop, chandelle, steep turn and lazy 8.

Sabrina Jackintell’s aircraft was a 1976 Grob G102 Astir CS glider (or sailplane), serial number 1171, FAA registration N75SW. The Astir CS is registered in the experimental category. It is approved for Day VFR Flight and may perform simple aerobatics: loop, chandelle, steep turn and lazy 8.

The Astir CS (“Club Standard”) is a single-seat performance sailplane, designed by Dipl.-Ing. Dr. Burkhart Grob e.K. and built by Burkhart Grob Flugzeugbau, Tussenhausen-Mattsies, Germany. The glider is built primarily of fiberglass. It has retractable landing gear and a T-tail.

The Astir CS was produced from 1974 to 1977. The current production variant of the G102 is the Astir III.

The Astir CS is 6,470 meters (21 feet, 2.7 inches) long with a wingspan of 15,000 meters (49 feet, 2.6 inches) and height of 1,26 meters (4 feet, 1.6 inches). The glider’s empty weight is approximately 255 kilograms (562 pounds). The maximum flying weight, with water ballast, is 450 kilograms, or 990 pounds. The minimum pilot weight is 70 kilograms, (154 pounds.) (Lighter pilots must carry ballast.) The Astir CS has a maximum speed (VNE) of 250 kilometers per hour (155 miles per hour). The glider is restricted to a maximum of +5.3 gs. Negative gs are prohibited.

N75SW was recently sold. It is currently registered to an individual in Southern California.

Sabrina Jackintell (née Sadie Patricia Paluga) was born at Youngstown, Ohio, 31 January 1940, the second child of John and Sadie M. Skvarka Paluga. Her father was a steel worker who had emigrated from Chekoslovakia. She attended Wilson High School in Youngstown. Miss Paluga was a member of the Art Students League at the school. One of her paintings was exhibited at the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, Ohio, in 1956. She was voted “Best Dancer” in 1957.

Miss Paluga graduated from the University of Florida, Gainesville, in 1960. While in college she began modeling and was featured on the cover of the fashion magazine, VOGUE.

In 1965 she drove Art Arfon’s jet-powered Green Monster land speed record car at the Bonneville Salt Flats, exceeding 300 miles per hour (483 kilometers per hour). Mechanical problems prevented the LSR machine from making a second pass in the opposite direction within the required time limit, so an official Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) Land Speed Record was not set.

During her life, she lived in Ohio, Florida, Colorado and Southern California. She was married to Jerry E. Jackintell, also from Youngstown, and a fellow student at the University of Florida. They had a son, Jerry, and daughter, Lori. They divorced in El Paso County, Colorado, 9 June 1982.

Sabrina Jackintell died at Sebring, Florida, 15 January 2012 at the age of 71 years.

¹ FAI Record File Number 348

© 2019, Bryan R. Swopes

Read the article about Sabrina Jackintell on Jonathan Turley’s Internet blog:

]]>Remarkable People: Sabrina Jackintell, a Woman for all Seasons

14 February 1932: Taking off from Floyd Bennett Field, Ruth Rowland Nichols flew Miss Teaneck, a Lockheed Vega 1 owned by Clarence Duncan Chamberlin, to an altitude of 19,928 feet (6,074 meters). This set a National Aeronautic Association record.

The airplane’s owner had flown it to 19,393 feet (5,911 meters) on 24 January 1932.

A contemporary newspaper reported:

RUTH NICHOLS SETS NEW ALTITUDE RECORD

Ruth Nichols’ flight in a Lockheed monoplane powered with a 225 horsepower Packard Diesel motor to an altitude of 21,350 feet Friday had been credited to the Rye girl unofficially as a new altitude record for Diesel engines. A sealed barograph, removed from the plane, has been sent to Washington to the Bureau of Standards to determine the exact altitude figure.

—The Bronxville Press, Vol. VIII, No. 14, Tuesday, February 15, 1932, Columns 1 and 2

RUTH NICHOLS SETS AIR MARK

Aviatrix Beats Chamberlain [sic] Altitude Record

Sails 21,300 Feet High in Flying Furnace

Temperature Found to Be 15 Deg. Below Zero

NEW YORK, Feb. 14. (AP)—Ruth Nichols, society aviatrix, flew Clarence Chamberlin’s “Flying Furnace” to a new altitude record, on the basis of an unofficial reading of her altimeter.

When she landed it registered 21,300 feet, while Chamberlin’s official record for the Diesel-motored craft was 19,363 feet.

Miss Nichols took off at 4:15 p.m. from Floyd Bennett airport and landed an hour and one minute later after an exciting flight.

She encountered temperatures of 15 degrees below zero, she said, and at 20,000 feet two of her cylinders blew out. At that height, too, she was forced to the use of her oxygen tank.

ENJOYED HER FLIGHT

In addition to the sealed barograph, which was taken from the plane at once to be sent to Washington for official calibration, Miss Nichols had three altimeters, two of which went out of commission in the upper atmosphere. The unofficial reading was taken from the third altimeter.

Despite her crippled engine and the fact that she had no brakes, she made a perfect landing and announced she had enjoyed the flight.

He unofficial altimeter reading was greater than that of Chamberlin after his flight and it is believed the official calibration would establish the new record for planes of this type.

ADVISED BY CHAMBERLIN

Chamberlin was present as her technical advisor, and he gave last-minute instructions as she stepped into the cockpit, wearing a heavy flying suit, lined boots, and a purple scarf wound about her head instead of a helmet.

The plane carried 13 gallons of furnace oil, and one tank of oxygen. The regular wheels were changed smaller, lighter ones before the flight.

Miss Nichols hold several records and has reached an altitude of 28,743 feet in a gasoline plane.

—Los Angeles Times, Volume LI. Monday, 15 February 1932, Page 3 at Column 3

Ruth Nichols’ Flight Record Confirmed

Rye, N. Y., March 2—Miss Ruth Nichols, aviatrix, received notice from Washington today that her altitude flight from Floyd Bennett Airport, Barren Island, on Feb. 14 last in a Diesel-powered airplane to a height of 19,928 feet has set a new American Altitude record for that type of plane.

—Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Vol. XCI, No, 61, Page 2, Column 2

Miss Teaneck had been modified. The original Wright Whirlwind engine had been replaced by an air-cooled, 982.26-cubic-inch-displacement (16.096 liter) Packard DR-980 nine-cylinder radial diesel-cycle (or “compression-ignition”) engine. The DR-980 had one valve per cylinder and a compression ratio of 16:1. It had a continuous power rating of 225 horsepower at 1,950 r.p.m., and 240 horsepower at 2,000 r.p.m. for takeoff. The DR-980 was 3 feet, ¾-inch (0.933 meters) long, 3 feet, 9-11/16 inches (1.160 meters) in diameter, and weighed 510 pounds (231 kilograms). The Packard Motor Car Company built approximately 100 DR-980s, and a single DR-980B which used two valves per cylinder and was rated at 280 horsepower at 2,100 r.p.m. The Collier Trophy was awarded to Packard for its work on this engine.

Miss Teaneck had been modified. The original Wright Whirlwind engine had been replaced by an air-cooled, 982.26-cubic-inch-displacement (16.096 liter) Packard DR-980 nine-cylinder radial diesel-cycle (or “compression-ignition”) engine. The DR-980 had one valve per cylinder and a compression ratio of 16:1. It had a continuous power rating of 225 horsepower at 1,950 r.p.m., and 240 horsepower at 2,000 r.p.m. for takeoff. The DR-980 was 3 feet, ¾-inch (0.933 meters) long, 3 feet, 9-11/16 inches (1.160 meters) in diameter, and weighed 510 pounds (231 kilograms). The Packard Motor Car Company built approximately 100 DR-980s, and a single DR-980B which used two valves per cylinder and was rated at 280 horsepower at 2,100 r.p.m. The Collier Trophy was awarded to Packard for its work on this engine.

The Lockheed Vega was a very state-of-the-art aircraft for its time. The prototype flew for the first time 4 July 1927 at Mines Field, Los Angeles, California.

The Lockheed Vega was a very state-of-the-art aircraft for its time. The prototype flew for the first time 4 July 1927 at Mines Field, Los Angeles, California.

The Vega used a streamlined monocoque fuselage made of strips of vertical-grain spruce pressed into concrete molds and bonded together with cassein glue. These were then attached to former rings. The wing and tail surfaces were fully cantilevered, requiring no bracing wires or struts to support them. They were built of spruce spars and ribs, covered with 3/32-inch (2.4 millimeters) spruce plywood.

The Lockheed Vega 1 was flown by a single pilot in an open cockpit and could carry up to four passengers in the enclosed cabin. It was 27.5 feet (8.38 meters) long with a wingspan of 41.0 feet (12.50 meters) and height of 8 feet, 6 inches (2.59 meters). The total wing area (including ailerons) was 275 square feet (25.55 square meters). The wing had no dihedral. The leading edges were swept slightly aft, and the trailing edges swept forward. The Vega 1 had an empty weight of 1,650.0 pounds (748.4 kilograms) and a gross weight of 3,200 pounds (1,452 kilograms).

The early Vegas were powered by an air-cooled, normally-aspirated 787.26-cubic-inch-displacement (12.901 liter) Wright Whirlwind Five (J-5C) nine-cylinder radial engine. This was a direct-drive engine with a compression ratio of 5.1:1. The J-5C was rated at 200 horsepower at 1,800 r.p.m., and 220 horsepower at 2,000 r.p.m. It was 2 feet, 10 inches (0.864 meters) long, 3 feet, 9 inches (1.143 meters) in diameter, and weighed 508 pounds (230.4 kilograms).

The early Vegas were powered by an air-cooled, normally-aspirated 787.26-cubic-inch-displacement (12.901 liter) Wright Whirlwind Five (J-5C) nine-cylinder radial engine. This was a direct-drive engine with a compression ratio of 5.1:1. The J-5C was rated at 200 horsepower at 1,800 r.p.m., and 220 horsepower at 2,000 r.p.m. It was 2 feet, 10 inches (0.864 meters) long, 3 feet, 9 inches (1.143 meters) in diameter, and weighed 508 pounds (230.4 kilograms).

The Vega had a cruising speed of 110 miles per hour (177 kilometers per hour) with the engine turning 1,500 r.p.m., and a top speed of 135 miles per hour (217 kilometers per hour)—very fast for its time. The airplane had a rate of climb of 925 feet per minute (4.7 meters per second) at Sea Level, decreasing to 405 feet per minute (2.1 meters per second) at 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). Its service ceiling was 15,900 feet (4,846 meters), and the absolute ceiling was 17,800 feet (5,425 meters). The airplane had a fuel capacity of 100 gallons (379 liters), giving it a range of 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) at cruise speed.

Twenty-eight Vega 1 airplanes were built by Lockheed Aircraft Company at the factory on Sycamore Street, Hollywood, California, before production of the improved Lockheed Vega 5 began in 1928 and the company moved to its new location at Burbank, California.

The techniques used to build the Vega were very influential in aircraft design. It also began Lockheed’s tradition of naming its airplanes after stars and other astronomical objects.

© 2021 Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

13 February 1950: Two Consolidated-Vultee B-36B Peacemaker long-range strategic bombers of the 436th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 7th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Strategic Air Command, departed Eielson Air Force Base (EIL), Fairbanks, Alaska, at 4:27 p.m., Alaska Standard Time (01:27 UTC), on a planned 24-hour nuclear strike training mission.

13 February 1950: Two Consolidated-Vultee B-36B Peacemaker long-range strategic bombers of the 436th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy), 7th Bombardment Wing (Heavy), Strategic Air Command, departed Eielson Air Force Base (EIL), Fairbanks, Alaska, at 4:27 p.m., Alaska Standard Time (01:27 UTC), on a planned 24-hour nuclear strike training mission.

B-36B-15-CF 44-92075 was under the command of Captain Harold Leslie Barry, United States Air Force.¹ There were a total of seventeen men on board.

Also on board was a Mark 4 nuclear bomb.

The B-36s were flown to Alaska from Carswell Air Force Base, Fort Worth, Texas, by another crew. The surface air temperature at Eielson was -40 °F. (-40 °C.), so cold that if the bomber’s engines were shut down, they could not be restarted. Crews were exchanged and the airplane was serviced prior to takeoff for the training mission. In addition to the flight crew of fifteen, a Bomb Commander and a Weaponeer were aboard.

After departure, 44-92075 began the long climb toward 40,000 feet (12,192 meters). The flight proceeded along the Pacific Coast of North America toward the practice target city of San Francisco, California. The weather was poor and the bomber began to accumulate ice on the airframe and propellers.

About seven hours into the mission, three of the six radial engines began to lose power due to intake icing. Then the #1 engine, outboard on the left wing, caught fire and was shut down. A few minutes later, the #2 engine, the center position on the left wing, also caught fire and was shut down. The #3 engine lost power and its propeller was feathered to reduce drag. The bomber was now flying on only three engines, all on the right wing, and was losing altitude. When the #5 engine, center on the right wing, caught fire, the bomber had to be abandoned. It was decided to jettison the atomic bomb into the Pacific Ocean.

The Mark 4 did not have the plutonium “pit” installed, so a nuclear detonation was not possible. The conventional explosives would go off at a pre-set altitude and destroy the bomb and its components. This was a security measure to prevent a complete bomb from being recovered.

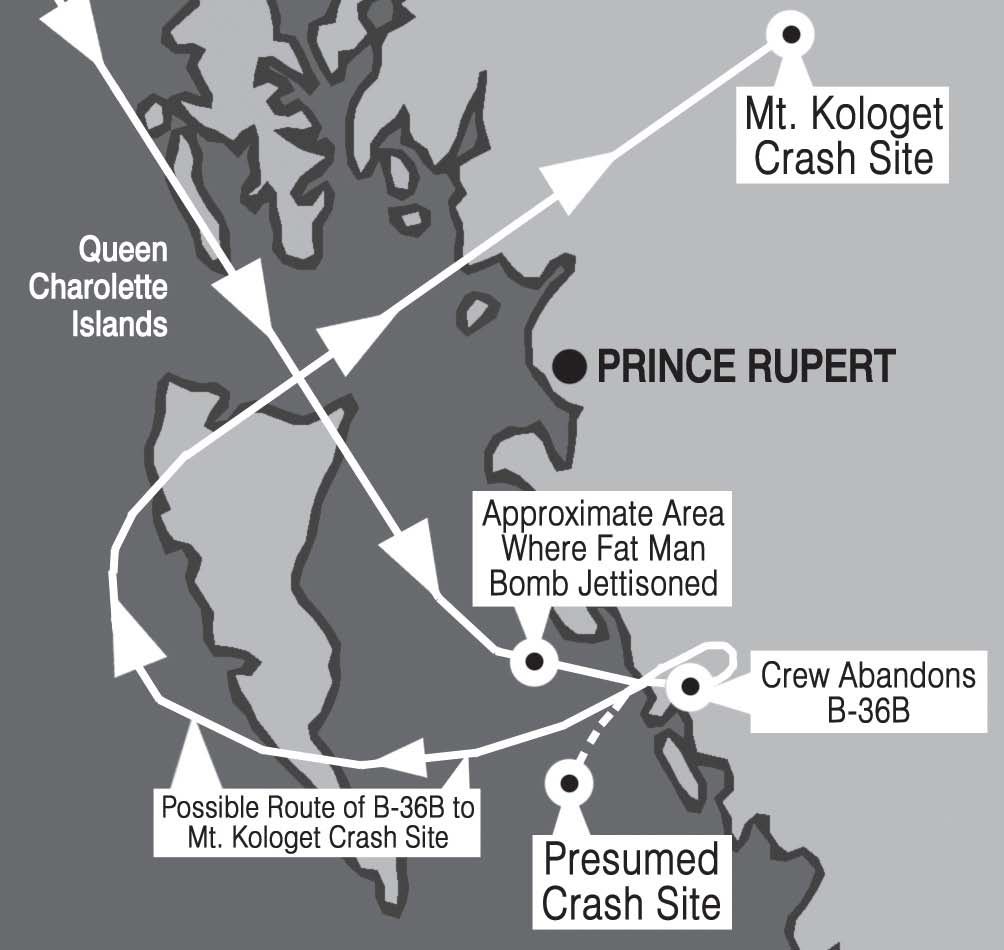

The bomb was released at 9,000 feet (2,743 meters), north-northwest of Princess Royal Island, off the northwest coast of British Columbia, Canada. It was fused to detonate 1,400 feet (427 meters) above the surface, and crewmen reported seeing a large explosion.

Flying over Princess Royal Island, Captain Barry ordered the crew to abandon the aircraft. He placed the B-36 on autopilot. Barry was the last man to leave 44-92075. Descending in his parachute, he saw the bomber circle the island once before being lost from sight.

Twelve of the crew survived. Five were missing and it is presumed that they landed in the water. Under the conditions, they could have survived only a short time. The survivors had all been rescued by 16 February.

It was assumed that 44-92075 had gone down in the Pacific Ocean.

On 20 August 1953, a Royal Canadian Air Force airplane discovered the wreck of the missing B-36 on a mountain on the east side of Kispiox Valley, near the confluence of the Kispiox and Skeena Rivers in northern British Columbia.

The U.S. Air Force made several attempts to reach the crash site, but it wasn’t until August 1954 that they succeeded. After recovering sensitive equipment from the wreckage, the bomber was destroyed by explosives.

The Mark 4 bomb was designed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). It was a development of the World War II implosion-type Mark 3 “Fat Man.” The bomb was 10 feet, 8 inches (3.351 meters) long with a maximum diameter of 5 feet, 0 inches (1.524 meters). Its weight is estimated at 10,800–10,900 pounds (4,899–4,944 kilograms).

The Mark 4 bomb was designed by the Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL). It was a development of the World War II implosion-type Mark 3 “Fat Man.” The bomb was 10 feet, 8 inches (3.351 meters) long with a maximum diameter of 5 feet, 0 inches (1.524 meters). Its weight is estimated at 10,800–10,900 pounds (4,899–4,944 kilograms).

The core of the bomb was a spherical composite of plutonium and highly-enriched uranium. This was surrounded by approximately 5,500 pounds (2,495 kilograms) of high explosive “lenses”—very complex-shaped charges designed to focus the explosive force inward in a very precise manner. When detonated, the high explosive “imploded” the core, crushing it into a smaller, much more dense mass. This achieved a “critical mass” and a fission chain reaction resulted.

The Mark 4 was tested during Operation Ranger at the Nevada Test Site, Frenchman Flat, Nevada, between 27 January and 6 February 1951. Five bombs were dropped from a Boeing B-50 Superfortress of the 4925th Special Weapons Group from Kirtland Air Force Base in New Mexico. The first four bombs were dropped from a height of 19,700 feet (6,005 meters) above ground level (AGL) and detonated at 1,060–1,100 feet (323–335 meters) AGL. Shot Fox was dropped from 29,700 feet (9,053 meters) AGL and detonated at 1,435 feet (437 meters) AGL. (Ground level at Frenchman Flat is 3,140 feet (957 meters) above Sea Level).

The Mark 4 was produced with explosive yields ranging from 1 to 31 kilotons. 550 were built.

Consolidated-Vultee B-36B-15-CF Peacemaker 44-92075 was completed at Air Force Plant 4, Fort Worth, Texas, on 31 July 1949. It had been flown a total of 185 hours, 25 minutes.

Consolidated-Vultee B-36B-15-CF Peacemaker 44-92075 was completed at Air Force Plant 4, Fort Worth, Texas, on 31 July 1949. It had been flown a total of 185 hours, 25 minutes.

The B-36B is 162 feet, 1 inch (49.403 meters) long with a wingspan of 230 feet (70.104 meters) and overall height of 46 feet, 8 inches (14.224 meters). The wings’ leading edges were swept aft 15° 5′ 39″. Their angle of incidence was 3°, with -2° twist and 2° dihedral. The empty weight is 137,165 pounds (62,217 kilograms) and the maximum takeoff weight was 326,000 pounds (147,871 kilograms).

With a wing area of 4,772 square feet (443 square meters) and 21,000 horsepower, the B-36 could fly far higher than any jet fighter of the early 1950s.

The B-36B was powered by six air-cooled, supercharged and turbocharged 4,362.49 cubic-inch-displacement (71.488 liter) Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major B4 (R-4360-41) four-row, 28-cylinder radial engines placed inside the wings in a pusher configuration. These had a compression ratio of 6.7:1 and required 115/145 aviation gasoline. Each engine was equipped with two General Electric BH-1 turbochargers. The R-4360-41 had a Normal Power rating of 2,650 horsepower at 2,550 r.p.m. Its Takeoff/Military Power rating was 3,500 horsepower at 2,700 r.p.m., with water/alcohol injection. The engines turned three-bladed Curtiss Electric constant-speed, reversible propellers with a diameter of 19 feet, 0 inches (5.791 meters) through a 0.375:1 gear reduction. The R-4360-41 is 9 feet, 1.75 inches (2.788 meters) long, 4 feet, 6.00 inches (1.372 meters) in diameter, and weighs 3,567 pounds (1,618 kilograms).

The B-36B was powered by six air-cooled, supercharged and turbocharged 4,362.49 cubic-inch-displacement (71.488 liter) Pratt & Whitney Wasp Major B4 (R-4360-41) four-row, 28-cylinder radial engines placed inside the wings in a pusher configuration. These had a compression ratio of 6.7:1 and required 115/145 aviation gasoline. Each engine was equipped with two General Electric BH-1 turbochargers. The R-4360-41 had a Normal Power rating of 2,650 horsepower at 2,550 r.p.m. Its Takeoff/Military Power rating was 3,500 horsepower at 2,700 r.p.m., with water/alcohol injection. The engines turned three-bladed Curtiss Electric constant-speed, reversible propellers with a diameter of 19 feet, 0 inches (5.791 meters) through a 0.375:1 gear reduction. The R-4360-41 is 9 feet, 1.75 inches (2.788 meters) long, 4 feet, 6.00 inches (1.372 meters) in diameter, and weighs 3,567 pounds (1,618 kilograms).

The B-36B Peacemaker had a cruise speed of 193 knots (222 miles per hour/357 kilometers per hour) and a maximum speed of 338 knots (389 miles per hour/626 kilometers per hour) at 35,500 feet (10,820 meters). The service ceiling was 43,700 feet (13,320 meters) and its combat radius was 3,710 nautical miles (4,269 statute miles/6,871 kilometers). The maximum ferry range was 8,478 nautical miles (9,756 statute miles/15,709 kilometers).

The B-36 was defended by sixteen M24A-1 20 mm automatic cannons. Six retractable gun turrets each each had a pair of 20 mm cannon, with 600 rounds of ammunition per gun (400 r.p.g.for the nose guns). These turrets were remotely operated by gunners using optical sights. Two optically-sighted 20 mm guns were in the nose, and two more were in a tail turret, also remotely operated and aimed by radar.

The B-36 was designed during World War II and nuclear weapons were unknown to the Consolidate-Vultee Aircraft Corporation engineers. The bomber was built to carry up to 86,000 pounds (39,009 kilograms) of conventional bombs in the four-section bomb bay. It could carry two 43,600 pound (19,777 kilogram) T-12 Cloudmakers, a conventional explosive earth-penetrating bomb. When armed with nuclear weapons, the B-36 could carry several Mk.15 thermonuclear bombs. By combining the bomb bays, one Mk.17 25-megaton thermonuclear bomb could be carried.

Between 1946 and 1954, 384 B-36 Peacemakers were built by Convair. 73 of these were B-36Bs, the last of which were delivered to the Air Force in September 1950. By 1952, 64 B-36Bs had been upgraded to B-36Ds.

The B-36 Peacemaker was never used in combat. Only four still exist.

¹ Captain Barry was killed along with other 11 crewmen, 27 April 1951, when the B-36D-25-CF on which he was acting as co-pilot, 49-2658, crashed following a mid-air collision with a North American F-51-25-NT Mustang, 44-84973, 50 miles (80 kilometers) northeast of Oklahoma, City, Oklahoma, U.S.A. The Mustang’s pilot was also killed.

© 2020, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>

Brigadier General Charles Elwood Yeager, United States Air Force, was born at Myra, Lincoln County, West Virginia, 13 February 1923. He was the second of five children of Albert Halley Yeager, a gas field driller, and Susan Florence Sizemore Yeager. He attended Hamlin High School, at Hamlin, West Virginia, graduating in 1940.

Chuck Yeager enlisted as a private, Air Corps, United States Army, 12 September 1941, at Fort Thomas, Newport, Kentucky. He was 5 feet, 8 inches tall (1.73 meters) and weighed 133 pounds (60 kilograms), with brown hair and blue eyes. He was assigned service number 15067845. Initially an aircraft mechanic, he soon applied for flight training. Private Yeager was accepted into the “flying sergeant” program.

Sergeant Yeager completed flight training at Yuma, Arizona, and on 10 March 1943, he was given a warrant as a Flight Officer, Air Corps, Army of the United States.

Assigned to the 363rd Fighter Squadron at Tonopah, Nevada, Flight Officer Yeager completed advanced training as a fighter pilot in the Bell P-39 Airacobra.

On 23 October 1943, while practicing tactics against a formation of Consolidated B-24 Liberator bombers, the engine of Yeager’s P-39 exploded. He wrote,

I was indicating about 400 mph when there was a roaring explosion in the back. Fire came out from under my seat and the airplane flew apart in different directions. I jettisoned the door and stuck my head out, and the prop wash seemed to stretch my neck three feet. I jumped for it. When the chute opened, I was knocked unconscious. . . I was moaning and groaning in a damned hospital bed. My back was fractured and it hurt like hell.

—Yeager: An Autobiography, Charles E. Yeager and Leo Janos, Bantam Books, Inc., New York, 1985, Chapter 3 at Page 21

When the 363rd deployed to England in November 1943, he transitioned to the North American Aviation P-51B Mustang. He named his P-51B-5-NA, 43-6762, Glamourus Glen, after his girlfriend. The airplane carried the squadron identification markings B6 Y on its fuselage. On 4 March 1944, he shot down an enemy Messerschmitt Bf-109G.

On his eighth combat mission, the following day, Yeager was himself shot down east of Bourdeaux, France, by Focke-Wulf Fw 190A 4 flown by Unteroffizier Irmfried Klotz.

. . . The world exploded and I ducked to protect my face with my hands, and when I looked a second later, my engine was on fire, and there was a gaping hole in my wingtip. The airplane began to spin. It happened so fast, there was no time to panic. I knew I was going down; I was barely able to unfasten my safety belt and crawl over the seat before my burning P-51 began to snap and roll, heading for the ground. I just fell out of the cockpit when the plane turned upside down—my canopy was shot away.

—Yeager: an Autobiography, by Charles E. Yeager and Leo Janos, Bantam Books, New York, 1985, Chapter 4 at Page 26.

Yeager was slightly wounded. His Mustang was destroyed. Over the next few months he evaded enemy soldiers and escaped through France and Spain, returning to England in May 1944. He returned to combat with a new P-51D-5-NA Mustang, 44-13897, which he named Glamorous Glenn II.¹ He later flew Glamorous Glen III, P-51D-15-NA Mustang, 44-14888.²

Flight Officer Yeager was commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant, Air Corps, Army of the United States, 6 July 1944. A few months later, 24 October 1944, he was promoted to the rank of captain, A.U.S. Between 4 March and 27 November 1944, Captain Yeager was officially credited with 11.5 enemy aircraft destroyed during 67 combat missions.

During World War II, Captain Yeager had been awarded the Silver Star with one oak leaf cluster (two awards); Distinguished Flying Cross; Bronze Star Medal with “V” (for valor); Air Medal with 6 oak leaf clusters (7 awards); and the Purple Heart.

With the end of the War in Europe approaching, Yeager was rotated back to the United States.

Captain Yeager married Miss Glennis Faye Dickhouse of Oroville, California, 26 February 1945, at at the Yeager family home in Hamlin, West Virginia. The double-ring ceremony was presided over by Rev. Mr. W. A. DeBar of the Trinity Methodist Church. “The pretty brunette was attired in a light aqua crepe dress of street length. Her accessories were black and her corsage was fashioned of yellow rosebuds.”

— Oroville Mercury-Register, Vol. 72, No. 56, Wednesday, 7 March 1945, Page 2, Column 3

On 10 February 1947, Captain Yeager received a commission as a second lieutenant, Air Corps, United States Army, with date of rank retroactive to 6 July 1944 (the date of his A.U.S. commission). He was promoted to first lieutenant on 6 July 1947. (These were permanent Regular Army ranks. Yeager continued to serve in the temporary rank of captain.) When the United States Air Force was established as a separate military service, 18 September 1947, Yeager became an Air Force officer.

Captain Yeager was assigned to the six-month test pilot school at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio. He took part in several test projects, including the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star and Republic P-84 Thunderjet. He also evaluated the German and Japanese fighter aircraft brought back to the United States after the war. Captain Yeager was then selected by Colonel Albert Boyd to fly the experimental Bell XS-1 rocket plane at Muroc Field in the high desert of southern California.

After a series of gliding and powered flights, on 14 October 1947, Captain Yeager and the XS-1 were dropped from a modified B-29 Superfortress at an altitude of 20,000 feet (6,048 meters). (Yeager had named his new rocket plane Glamorous Glennis.) Starting the 4-chambered Reaction Motors rocket engine, Yeager accelerated to Mach 1.06 at 42,000 feet. He had “broken” the Sound Barrier.

Yeager made more than 40 flights in the X-1 over the next two years, exceeding 1,000 miles per hour (1,610 kilometers per hour) and 70,000 feet (21,336 meters). He was awarded the Mackay and Collier Trophies in 1948. In 1949, the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale awarded its Gold Medal to Captain Yeager. General Yeager’s gold medal is in the collection of the Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum, along with the Bell X-1 rocket plane, Glamorous Glennis.

The X-1 was followed by the Bell X-1A. On 12 December 1953, Major Yeager flew the new rocket plane to 1,650 miles per hour (2,655 kilometers per hour), Mach 2.44, at 74,700 feet (22,769 meters).

After the rocket engine was shut down, the X-1A tumbled out of control—”divergent in three axes” in test pilot speak—and fell out of the sky. It dropped nearly 50,000 feet (15,240 meters) in 70 seconds. Yeager was exposed to accelerations of +8 to -1.5 g’s. The motion was so violent that Yeager cracked the rocket plane’s canopy with his flight helmet.

Yeager was finally able to recover by 30,000 feet (9,144 meters) and landed safely at Edwards Air Force Base.

Yeager later remarked that if the X-1A had an ejection seat he would have used it.

Bell Aircraft Corporation engineers had warned Yeager not to exceed Mach 2.3.

During the Korean War, Major Yeager test flew a captured North Korean Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 fighter. Its pilot, Lieutenant No Kum-Sok, had flown it to Kimpo Air Base, Republic of South Korea, on 21 September 1953.

On 17 November 1954, in a ceremony at The White House, President Dwight D. Eisenhower presented the Harmon International Trophy to Major Yeager, for his Mach 2.44 flight. His friend, Jackie Cochran, was awarded the Harmon Aviatrix Trophy at the same time.

In 1954, Major Yeager was assigned to command the 417th Fighter Bomber Squadron at Hahn Air Base, Germany. The 417th flew the North American Aviation F-86H Sabre.

In 1958, Lieutenant Colonel Yeager assumed command of the 1st Fighter Day Squadron at George Air Force Base, Victorville, California, which was equipped with the North American Aviation F-100 Super Sabre.

Yeager attended the Air War College at Maxwell AFB, Montgomery, Alabama, graduating in June 1961.

On 23 July 1962, Colonel Yeager returned to Edwards Air Force Base to become commandant of the Aerospace Research Pilot School.

The Aerospace Research Pilots School trained all of the U.S. military’s astronaut candidates. One of the training aircraft was the Aerospace Trainer (AST), a highly-modifies Lockheed NF-104A Starfighter. The AST was equipped with a rocket engine and a reaction control system to provide pitch, roll and yaw control when at very high altitudes where the normal aircraft flight controls could not function.

On 10 December 1963, Colonel Yeager was flying an AST, 56-762, on a zoom climb profile, aimingg for an altitude record at approximately 120,000 feet ( meters). He reached only 108,000 feet (32,918 meters) however. On reentry, the AST’s pitch angle was incorrect and its engine would not restart. The airplane went into a spin.

Yeager rode the out-of-control airplane down 80,000 feet (24,384 meters) before ejecting.

The data recorder would later indicate that the airplane made fourteen flat spins from 104,000 until impact on the desert floor. I stayed with it through thirteen of those spins before I punched out. I hated losing an expensive airplane, but I couldn’t think of anything else to do. . . I went ahead and punched out. . . .

— Yeager, An Autobiography, by Brigadier General Charles E. Yeager, U.S. Air Force (Retired) and Leo Janos, Bantam Books, New York, 1985, at Pages 279–281.

Colonel Yeager commanded the 405th Fighter Wing at Clark AFB, Philippine Islands, in July 1966. He flew 127 combat missions over Vietnam with the Martin B-57 Canberra light bomber.

Returning to the United States in February 1968, Colonel Yeager took command of the 4th Tactical Fighter Wing, Seymour Johnson AFB, North Carolina. The 4th deployed to the Republic of Korea during the Pueblo Crisis.

Colonel Yeager was promoted to the rank of brigadier general, 1 August 1969 (date of rank 22 June 1969). He was appointed vice commander, Seventeenth Air Force, at Ramstein Air Base, Germany.

Brigadier General Yeager served as a U.S. defense representative to Pakistan from 1971 to 1973. He was then assigned to the Air Force Inspection and Safety Center, Norton AFB, near Riverside, California. He took command of the center June 1973.

Brigadier General Yeager made his final flight as an active duty Air Force pilot in a McDonnell Douglas F-4E Phantom II at Edward Air Force Base, 28 February 1975. During his career, General Yeager flew 180 different aircraft types and accumulated 10,131.6 flight hours. He retired the following day, 1 March 1975, after 12,222 days of service.

Chuck Yeager’s popularity skyrocketed following the publication of Tom Wolfe’s book, The Right Stuff, in 1979, and the release of The Ladd Company’s movie which was based on it. (Yeager had a “cameo” appearance in the film.) He became a spokesperson for AC Delco and the Northrop Corporation’s F-20 Tigershark lightweight fighter prototype. In 1986 and 1988, he drove the pace car at the Indianapolis 500. Yeager co-wrote an autobiography, Yeager, with Leo Janos, published in 1985, and followed in 1988 with Press On!, co-authored by Charles Leerhsen.

In 1986, President Ronald Reagan appointed General Yeager to the Rogers Commission investigating the Challenger Disaster.

Glennis Yeager passed away 22 December 1990 at Travis Air Force Base, Sacramento, California.

TDiA was present at Edwards Air Force Base, 14 October 1997, on the 50th Anniversary of Yeager’s flight breaking the sound barrier. Flying in the forward cockpit of a McDonnell Douglas F-15D Eagle, with co-pilot Lieutenant Colonel Troy Fontaine and wingman Bob Hoover in a General Dynamics F-16 chase plane, Yeager again left a sonic boom in his path as he flew over the high desert.

On 22 August 2003, Chuck Yeager married Ms. Victoria Scott D’Angelo in a civil ceremony at Incline Village, Nevada.

Brigadier General Charles Elwood Yeager, United States Air Force (Retired) died at a hospital in Los Angeles, California, 7 December 2020, at the age of 97 years. His remains are buried at the Lincoln Memorial Cemetery, Myra, West Virginia.

¹ Glamorous Glenn II had initially been assigned to Captain K. Peters, who had named it Daddy Rabbit. The fighter crashed in bad weather 18 October 1944. 2nd Lieutenant Horace M. Roycroft was killed.

² Glamorous Glen III, renamed Melody’s Answer, was lost in combat 2 March 1945, south of Wittenburg, Germany. Its pilot, Flight Officer Patrick L. Mallione, was killed in action. (MACR 12869)

© 2021, Bryan R. Swopes

]]>By Sean M. Cross, CAPT, USCG (retired)

“Lewis had to make what he considered to be one of the most crucial decisions of his life. Peering at the fog below him, he remembers asking himself a question to plunge or not to plunge…”

TODAY IN COAST GUARD AVIATION HISTORY – 12 FEBRUARY 1971: an HH-3F #1473 assigned to Air Station San Diego, CA and crewed by LCDR Paul R. Lewis (AC), LT Joseph O. Fullmer (CP), ASM3 Larry E. Farmer (FM), AT3 Charles Desimone (AV) and HM3 Richard M. McCollough (AMS) launched in response to an injured or ill “seaman in need of an operation” ¹ from the 492-foot freighter STEEL EXECUTIVE, approximately 220 miles south of San Diego. The WWII-era Type C3-class cargo ship owned by Isthmian Lines, Inc. of New York was on an extended trip from Saigon, South Vietnam to New York City via the Panama Canal with stops in Astoria, OR and various east coast ports. They departed Saigon on 29 January 1971 and on 12 February were southbound for the Panama Canal.² After requesting assistance, the ship reversed course back toward San Diego to reduce transit distance for the helicopter. This is their story.

Friday afternoon at around 4:00 PM, Rescue Coordination Center Long Beach launched the off-going Air Station San Diego HH-3F duty crew on a long range medical evacuation or MEDEVAC. The maintenance crew had to stop downtown vehicle traffic so that #1473 could taxi from the unit’s waterfront location across Harbor Drive to Lindberg Field in order to utilize the runway for a running takeoff – as the aircraft could not get airborne from a hover with a maximum fuel load.³ According to LCDR Lewis, taking off “out of San Diego, it was a clear afternoon,” ⁴ but the sun was lowering in the sky with official sunset at 5:31 PM.

After two hours of night overwater navigation and using a combination of radio direction finding, helicopter radar, and guidance from the STEEL EXECUTIVE, #1473 arrived in the vessel’s vicinity, but was unable to make visual contact through the dense fog which extended from the surface to about 700 feet above the water.

Flight mechanic Larry Farmer described the scene, “We flew over the estimated position at 1,500 feet and it was beautiful, you could see stars clear to either horizon, but glancing down – it looked like a huge layer of thick cotton blanketing the water below us.” ⁵

With visibility less than 1/8 mile, the helicopter directed the vessel to turn on all available topside lighting and dropped two MK-58 marine location markers (floating cylinder that produces smoke and flames for 40-60 minutes) approximately two miles downwind to assist in executing an instrument approach to a hover above the water’s surface. ⁶

Lewis had to make a crucial decision. Peering at the fog below him, he remembers asking himself a question to plunge or not to plunge. ⁷ Lewis knew that the answer could spell a chance at life for the seriously ill merchant seaman. However, there was also his crew, his co-pilot, a radio operator, a corpsman and the aviation survivalman who operated the rescue hoist. Their lives and his own also were at stake. “I decided to lower the helicopter down to the water,” he said in an interview. “By then it was pitch dark. I flew away from where our radar told us the ship was and then went down to about 40 feet from the ocean.” ⁸

To transition from forward flight to a hover, #1473 executed a challenging “beep-to-hover” maneuver, which enabled them to safely approach the water and the ship. The “beep-to-hover” maneuver was developed by LCDR Frank Shelley, test pilot and program manager for HH-52A acquisition testing, to help pilots safely transition to an overwater hover at night and/or in instrument conditions. The HH-3F PATCH (precision approach to a coupled hover) eventually replaced the “beep-to-hover” in late-1971. ⁹ Interestingly, both procedures most closely mimic the ‘early’ MATCH (manual approach to a controlled hover) in the H-60 and H-65 series aircraft – the PATCH and CATCH in these aircraft utilize auto-pilot and trim functions to perform a ‘hands off’ coupled approach to the water.

This “beep-to-hover” maneuver can be disorienting in the clouds at night, particularly when low over the water with little room for error. Both pilots must continuously scan and interpret the flight instruments – this is critically important – while smoothly manipulating the controls to ensure they are hitting various airspeed and altitude windows to fly the correct profile.

At the completion of this very demanding approach, the helicopter crew found itself in nearly “zero-zero” weather but had executed the approach with such precision that the MK-58s were located. ¹⁰ Barely establishing visual reference with the ocean surface from a 40-foot hover, the helicopter crew was unable to see the vessel’s lights and therefore was hovering at night in a dense fog with minimal visual reference with the ocean surface.

“We made what amounted to an instrument approach to the water,” Lewis explained, “Hovering just over the waves we crawled toward the ship which was about two to three miles away.” ¹¹ At least that’s where a little black box on the instrument panel said the ship was. The aircrew inched forward using the helicopter doppler hover system, the radar, the RDF (radio direction finding, which provided a bearing to a radio signal from the ship). At about one mile out, the STEEL EXECUTIVE’s blip on the helicopter radar was lost in surface clutter – the mood was tense with the aircrew concerned about the combination of low visibility, closure rate, low altitude and vessel rigging obstacles. ¹² At an altitude of 40 feet in extremely limited visibility, the helicopter could literally stumble into the vessel, causing a collision that would doom everyone on board the aircraft and imperil the ship’s crew as well. Eventually, the ship’s surface search radar picked up the helicopter and guided it to her. ¹³ Farmer was on a gunner’s belt leaning out the cabin door and straining to find the ship’s glow. ¹⁴

Lewis praised ASM2 Larry Farmer for far exceeding the scope of duties he’d been trained for – hoisting the injured man off his ship and onto the hovering aircraft. “Farmer actually guided me to the ship.” Lewis said, “I had no visual references so I depended entirely on him. He became our aircraft’s eyes and brought us over the freighter.” ¹⁵

Pucker factor is a slang phrase used by military aviators to describe the level of stress and/or adrenaline response to danger or a crisis situation. The term refers to the tightening of the sphincter caused by extreme concern – on particularly challenging missions, the seat cushions might go missing altogether. The pucker factor had been high since the initial descent into the fog bank, however Farmer remarked that “finally gaining a visual with the ship eased the pucker factor and transformed the aircrew’s outlook from uncertainty of success to ‘we can do this’.” ¹⁶

Huge spotlights pierced the fog, but all Lewis and Farmer could see was the hoist аrеа. Even under ideal weather conditions, positioning a hovering helicopter over the crowded decks of a freighter is a delicate maneuver. “Doing it in pitch darkness while howling 25-mile an hour winds rock ship and aircraft alike is – in the words of the young crewmen who were there with Lewis – something else”. ¹⁷

The pilot and flight mechanic were still concerned with the helicopter’s low hoisting altitude as they surveyed the vessel obstacles – the ship’s towering rigging literally disappeared in the fog above. ¹⁸ Much of the obstacle clearance judgement and decision making fell on the flight mechanic’s shoulders as the pilot was unable to see the hoisting area behind him. The crew was convinced that a ‘basket with trail line’ was the right technique for the situation as it would allow the helicopter to hoist from a position offset 30-40 feet from the ship and facilitate Lewis’ use of the STEEL EXECUTIVE as a hover reference. A trail line is a 105-foot piece of polypropylene line (similar to a water ski rope) with a 300-pound weak-link at one end and a weight bag at the other. The weight bag end of the trail line is paid out below the helicopter and delivered to the persons in distress (usually vertically, but seasoned flight mechanics can literally ‘cast’ the weight bag to a spot). The weak link is then attached to the hoist hook and the helicopter backs away until the pilot can see the hoisting area. The persons in distress can then pull the basket to their location – creating a hypotenuse or diagonal – as opposed to a purely vertical delivery.

Farmer carefully conned the helicopter over the vessel providing voice commands to the pilot – delivering the trail line and, subsequently, the rescue basket to the stern of the STEEL EXECUTIVE. The semi-ambulatory patient was assisted into the basket by the ship’s crew and then hoisted aboard the helicopter. Lewis and Farmer were able to complete the hoist on the first attempt. Farmer appreciatively described Desimone’s efforts: “he spent most of his time working the radios, but he assisted me during the hoists. He was the extra set of hands getting the rescue basket into the cabin and then clearly directed the patient to the back of the cabin.” ¹⁹ Petty Officer McCollough secured the patient for the flight, administered antibiotics and maintained constant watch on the patient’s condition during the return flight. ²⁰

Often forgotten was the job done by Fullmer as Safety Pilot. He continuously scanned the system instruments to ensure the aircraft was operating normally and monitored the flight instruments to ensure obstacle clearance and safe altitude. He effectively conveyed critical information without interfering with Farmer’s conning commands. ²¹

After completing the hoist, it took a few minutes to secure the cabin – Farmer stowed the basket and secured the hoist hydraulics, then closed the cabin door and reported the cabin was secured and ready for forward flight. The pilots then executed a demanding night instrument take-off or ITO from a hover over the water. The ITO is similar to the “beep-to-hover” in terms of relying on aircraft instruments instead of visual cues, but its purpose is the opposite – to get you away from the water and into a forward flight profile at a safe airspeed and altitude. The maneuver was flawlessly executed and the aircrew soon found themselves above the fog bank in clear skies. The helicopter returned to San Diego to deliver the patient to medical authorities. The STEEL EXECUTIVE crewman subsequently recovered. ²²

LCDR Lewis earned the Distinguished Flying Cross for this mission, while ASM3 Farmer earned the Air Medal. The medals were presented by RADM James Williams, Commander, 11th Coast Guard District, in a ceremony at Air Station San Diego on 23 February 1972.

The Lewis and Farmer citations are below:

LCDR Lewis also earned the American Helicopter Society (now the Vertical Flight Society) Frederick L. Feinberg Award on 19 May 1972 at the Sheraton-Park Hotel, Washington, D. C – presented to the pilot or crew of a vertical flight aircraft who demonstrated outstanding skills or achievement during the preceding 18 months.

LCDR Lewis also earned the American Helicopter Society (now the Vertical Flight Society) Frederick L. Feinberg Award on 19 May 1972 at the Sheraton-Park Hotel, Washington, D. C – presented to the pilot or crew of a vertical flight aircraft who demonstrated outstanding skills or achievement during the preceding 18 months.

The award was presented by RADM William A. Jenkins, Chief, Office of Operations, Coast Guard Headquarters, who outlined the case as follows:

“Commander Lewis was selected for his sea rescue of an ill crewman from the merchant ship, S.S. Steel Executive, at night and under extremely hazardous weather conditions. Despite very dense fog, Lt. Cdr. Lewis took off and proceeded to the estimated position of the vessel some 220 miles south of San Diego, Calif. , and — by applying extremely skillful instrument approach procedures — was able to find the vessel with visibility reduced to an eighth of a mile and less at times, and by hovering 50 feet above the vessel, he rescued its seriously ill crewman and safely delivered the patient to medical authorities. The crewman subsequently recovered. This demonstration of courage, skill and airmanship has deservingly earned him the Frederick L. Feinberg Award.” ²³

LCDR Lewis provided the following acceptance speech:

LCDR Lewis provided the following acceptance speech:

“It’s indeed a deep personal honor for me to receive this award from the American Helicopter Society and from the Kaman organization. But in a sense I really feel that it’s unfortunate that this award should be given to an individual. Without attempting to feign false modesty, I sincerely feel that this award should be shared with many others; specifically the other 3 members of my crew, my service — the Coast Guard — and really, in a sense, you, the members of the American helicopter industry. I am sure there are people sitting here in the audience this evening that participated in the design, the development, and the production of the very fine Sikorsky HH-3 helicopter that was used in this rescue. In honoring the Coast Guard by my selection, I really feel that you honored a service that from the helicopters very beginning — we employed it to rescue thousands of people and saved millions of dollars of property. My rescue that is honored here this evening is really very typical of many other rescues that the Coast Guard has accomplished. And so — even though it’s my name alone that is on this award — I sincerely believe that the honor belongs to my entire crew for that evening that this rescue was accomplished and I feel also that it should be shared with the many other Coast Guard crews who accomplished many other rescues of equal ability or what may it be, but I feel I should share the honor with them.” ²⁴

Later that summer (1972), LCDR Lewis transferred to Air Station St. Petersburg, FL where he continued flying the HH-3F helicopter. Unfortunately, six months after the Feinberg Award presentation, on 16 December 1972, HH-3F #1474 assigned to Air Station St. Petersburg was lost off Sarasota along with the crew LCDR Paul R. Lewis, MAJ Marvin A. Cleveland, USAF (Exchange pilot), AD1 Edward J. Nemetz, AT3 Clinton A. Edwards, and four rescued crewmen from the 54-foot fishing vessel WANDA DENE William Peek, George Dayhoss, Herbert Hardy and Paul Manley. It was late on Saturday when the WANDA DENE, sent out a distress call. The stricken vessel was 35 miles southwest of Key West, taking on water and sinking in rough seas. HH-3F #1474 was launched with its crew of four for a long range rescue. The helicopter arrived overhead the WANDA DENE several hours later and successfully hoisted the four crewmen from the sinking vessel in challenging conditions. The #1474 then flew to Naval Air Station Key West to refuel. From there #1474, now with eight people aboard, departed at about 7 PM for a return flight to St. Petersburg. Normal flight operations were reported with regular radio position reports until about 8:30 PM. Two days later a small portion of the helicopter was found in the Gulf of Mexico south of Fort Myers. Despite a massive search, very little of the aircraft and only one body, that of one of the fisherman, was ever recovered. The cause of the crash was never determined.

On 04 March 2011, a dedication ceremony was held at Air Station Clearwater, FL to posthumously name an annex building in honor of the Service and Sacrifice displayed by LCDR Paul R. Lewis. Members of the Lewis Family including daughter Kara Lewis, wife, Jackie Lewis, sister Abby Sauer, son Curt Lewis, daughter Megan Lewis, sister Joan Chaffee, and Abby’s husband, Gene Sauer were in attendance. Here is a section of the presentation that was made that day: