From this moment on

Some thoughts on the Beatles' new/old/new "Real Love" and the trippiness of time

I don’t wish, and I certainly don’t need, to add to all of the talk about the Beatles re-released Anthology collection, only to remark at the predictable blend of rapture and furor that the band’s reissues tend to inspire. From overpraise out of the mouths of blinkered apostles to dismissive complaints from skeptical fans about what was and/or wasn’t included (or excluded), everyone’s had an opinion. (I listened to the newly released outtakes, and was generally underwhelmed. A new hour’s worth of video has been added to Anthology. While it’s fantastic, again, to watch the fellas chat and to reminisce, and to fool around in the studio with George Martin listening to old masters, my favorite moment comes from the reliably wry George Harrison: while listening to the august horns reprise the chorus in “You Never Give Me Your Money,” Harrison throws a side eye at the camera and mutters, “A bit cheesy, that.”)

Since the release two years ago of “Now and Then”—a demo recorded by John Lennon in the late-1970s and messed around with by Paul McCartney, Harrison, and Ringo Starr in the mid-1990s, then renewed in the digital domain via machine learning–assisted audio restoration technology—many have been looking forward to remixes of “Free As a Bird” and “Real Love,” originally released in 1995 and ‘96, respectively, hopeful that A.I. might similarly clean up and rescue Lennon’s lo-fi vocals that marred those tracks. The new mix of “Free As a Bird” does sound great—Lennon sounds remarkably clear and up-front, and McCartney and Harrison’s sung verses don’t sound nearly as jarringly contemporary as they did in the original mix. The whole thing’s well balanced, and warmer. Though I agree with the late, great Ian MacDonald’s charge that co-producer Jeff Lynne’s trademark “soaking” of the mid-‘90s tracks with a “texture of Eighties synth ‘pad’ and massed acoustic guitars” created a sound that’s “soggily un-Beatleish’—still among my favorite of MacDonald’s cutting gripes—“Free As a Bird” indeed sounds like a Fab Four song now, not some theoretical lab creation.

Yet as someone who genuinely liked “Real Love,” I’m disappointed with what’s been done to it in Lynne’s so-called “de-mixed” new version. (And I’m not alone.) For one, the song is inexplicably shorter, and McCartney and Harrison’s wonderful—indeed, very Beatlesish—harmonies are thinned and mixed too low throughout the track. The result is that “Real Love” sounds more like a Lennon solo song then a Beatles song (which it isn’t, detractors insist, and which, ironically, is closer in spirit anyway to Lennon’s original intentions, as he likely wasn’t imagining collaborating with his old partners when he cut these demos). Many have complained about Lynne and company’s curious decision to alter the vocal tracks that were used in the original mix, and to present Lennon’s vocal so dryly, without the thickening of double tracking that Lennon himself loved so much, to the point that he drove his harried engineers to essentially invent ADT (automatic double tracking) in the mid-‘60s. The new production team also decided to stick with the original decision to speed up “Real Love”; there are several fan-produced mixes online that slow down the track to the speed at which the song was originally recorded. I prefer them to Lynne’s.

Worse, to my ears, is that much of Harrison’s guitar playing was edited out in the new mix. As I wrote two years ago at No Such Thing As Was about “Real Love,” the most surprising and poignant reveal in the new song was “the unintended legacy to Harrison’s guitar playing.”

The spotlight of the song, as in “Free As A Bird,” was duly aimed at Lennon’s miraculous reappearance; yet the heart of the song is George’s characteristically-tasteful and emotionally-rich playing. His lovely phrases answering Lennon’s lines in the verses and the chorus both evoke his unobtrusive playing on mid-1960s Beatles records and respond beautifully to the sentiments Lennon was working though alone in his room at the Dakota a decade later, having secluded himself from his mates. Harrison’s playing on “Real Love” is among his most affecting on any Beatles track, I feel. That was amazing and wholly surprising to me, but it shouldn’t have been. While in the Beatles, Harrison nearly always rose to a song’s emotional state, where it had taken the songwriter, where it was taking Harrison, and where it would take a listener sometime in the future. You’re hearing those songs right now, as am I.

All their little plans and schemes

Time is a perpetual motion machine. And consider, also, its alarming elasticity. With the Beatles’ release of “Now and Then,” we’re as far from “Free As A Bird” now as “Free As A Bird” was from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. And an analogy suggests itself: “Free As a Bird” and “Real Love” are to

Alas, some of those moments have been erased, a loss that was magnified while watching McCartney and Harrison in the new Anthology episode, on acoustic and electric guitars, navigate their way around Lennon’s demo, bouncing ideas off of each other, some sticking, some not. It’s a privilege to watch Harrison compose his solos, led by craft and affection and, presumably, Lennon’s disembodied voice. When in the mood, I’ll be playing my original seven-inch single of “Real Love,” A.I. be damned.

I guess that I ended up adding to all of the talk about Anthology, after all. I observed at No Such Thing As Was back when “Now and Then” was released that we were as far from “Free As a Bird” as “Free As a Bird” was from Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. That’s amazing, an ordinary, extraordinary discovery. It’s fascinating what time does, how perspective can stretch. In the 1960s, the Beatles increasingly rebelled against the limitations of studio and recording technology, pushing themselves and their engineers into surprising places as they led with their imagination: finding ways to create the sounds in their futuristic heads with increasingly archaic studio equipment. (They were hardly alone in this, of course, just the most high-profile band.) And now: from the vantage point of 2025, we gaze back at McCartney, Harrison, Starr, Lynne, and their crew in the mid-1990s struggling against the limitations of technology; they did their best with what was then state-of-the-art digital domain, and yet now those attempts sound virtually antiquated, are certainly obsolete, anyway, the equivalent to mid-‘60s studio striving. Artificial Intelligence and learning machine software were far, far away. Those mid-‘90s songs carry their own sweet burden of nostalgia now.

As I’m thinking about all of this, the 60th anniversary of the release of Rubber Soul came and went, and with it the avalanche of praise and tributes. On that album, the Beatles were leaning toward a future packed with inward gazing and trippy soundscapes; it’s a record very much of its era as it’s also unbounded, fresh to our ears and hearts today. The Beatles’ music, it seems, isn’t beholden to the rules and laws of time. The band members long ago reached a cultural significance that spoke and continues to appeal to millions around the world, allowing many to think and to speak through the songs.

In 2020, the German fiction writer and opera director Jenny Erpenbeck published Not a Novel: A Memoir in Pieces, translated by Kurt Beals, a gathering of small essays, occasional lectures, and the like. One of the pieces is titled “John,” originally published in 2012. In it, Erpenbeck relates a strange episode from her past. One day, when she was a young woman, the phone rang in her home. The caller refused to identity himself; instead, he wanted to play her something, and played her the Beatles’ “Michelle.” The telephone rang another time; same deal, the caller wouldn’t say his name, only that he wanted to play Erpenbeck something, and he played “Yesterday.” “This goes on for weeks,” she writes. “How do we know each other? I’m not telling. A Hard Day’s Night. I’m going to hang up if you don’t tell me your name. You can call me John. Yellow Submarine. Like John Lennon. But what’s your real name? I’m not telling.”

One day, a letter arrived in the mail: “You are like a flower, so fair and fine and pure.” The letter didn’t have a stamp. “How do we know each other? Guess. P.S. I Love You. We talk about music. We talk about the cold world of adults. We talk about the nuclear threat.” A letter arrived with the word “peace” repeated more than seventy times, arranged so as to form the letters of Erpenbeck’s name. “I get used to these calls from John Lennon,” she writes. “I lay the receiver on the table and let the music play while I do my homework. I want to hold your hand.” One day, a different kind of letter arrives, an official looking letter “that lists all of the people who entered or exited the high-rise where I live on a given Wednesday between 3 and 5 p.m. 1 man in a light coat (exiting). 1 woman with a string shopping bag (entering). 2 children (exiting). 1 old woman with a dog (exiting), etc. The list is long. I don’t appear on the list, and neither does my mother. I was at a friend’s house that afternoon, my mother didn’t enter or exit. Why do you sit there for hours? Why did you do that? Love, lo-o-ove, love. Do you even know what I look like? Do you want to know a secret. Do we know each other?” Is John Lennon stalking her?

Erpenbeck was born and raised in East Berlin. The decade after Lennon stopped contacting her, the Wall had fallen, Germany had been reunified, reform was in the air. Since 1950, the Stasi operated covertly as Germany’s secret police, intelligence agency, and crime investigation service. It was eliminated in 1990. The following year, in the spirit of rehabilitation, the government enacted the Stasi Records Act, which resulted in the Stasi Records Agency, a government bureau where German citizens were able to request a look at files that the Communist German Democratic Republic may have kept on them down the decades. Erpenbeck requested her file. In the event, it wasn’t “very thick. One of the few pages contains my personal information with the comment: Pacifist. I’m surprised.” She turned the page and noticed the “peace” anagram, the list of the people who entered and departed her building a decade earlier, and other familiar items.

The takeaway: “This is probably the only case in Stasi history when the surveillance authority intercepted a letter from a high school boy who kept a high school girl’s house under surveillance because he was in love with her.” She adds, “From my Stasi file, a part of my youth that I had almost forgotten looks back at me. One day, just when I least expected it, John finally revealed his identity after all. His real name was Sebastian, and he was a skinny, pale boy who had fallen in love with me when i played a mermaid in a pageant at summer camp.”

How common the language “John Lennon” is—the name, and the songs that Lennon, McCartney, and Harrison wrote, and all they signify, transcend culture and politics, lies and truths. Ian Leslie writes persuasively in John & Paul: A Love Story in Song that, “More than half a century after they stopped making music, the Beatles continue to permeate our lives. We listen to their songs while driving and dance to them in clubs and in kitchens; we sing them in nurseries and in stadiums; we cry to them at weddings and funerals and in the privacy of bedrooms. They are not likely to be forgotten anytime soon; if anything of our civilization is remembered a thousand years from now, there is a good bet it will be the chorus of ‘She Loves You’ and an image of four men crossing a street in single file.” Erpenbeck’s past was cloaked in secrets, and then, quite literally, made public. The Beatles were along for the ride.

You might also dig:

Gotta hear it again today

I recently scored a clean copy of an original, 1964 pressing of The Beatles’ Second Album, a record that I grew up with. The songs remain as powerful and meaningful to me now as they were when I was a kid, when the top of my head came off as the record spun in my family’s rec room. I was especially happy to get ahold of a nice copy of this album—I belie…

A boy like me

In 1966, the popular Italian singer Gianni Morandi released the single “C’era un ragazzo che come me amava i Beatles e i Rolling Stones,” translated as “There was a Boy like Me who Loved the Beatles and the Rolling Stones.” The story of the celebrated song coming into being is a familiar one of happenstance and luck. At the

The cries of freedom

I’ve been working on my next music essay for The Normal School about Robyn Hitchcock’s memoir 1967 and his companion album of cover songs released a few months later. (Look for my piece soon!) As if fated, the Soft Boys’ “Positive Vibrations” popped up on Shuffle the other day. I bet that Robyn would have something both whimsical and profound to say abo…

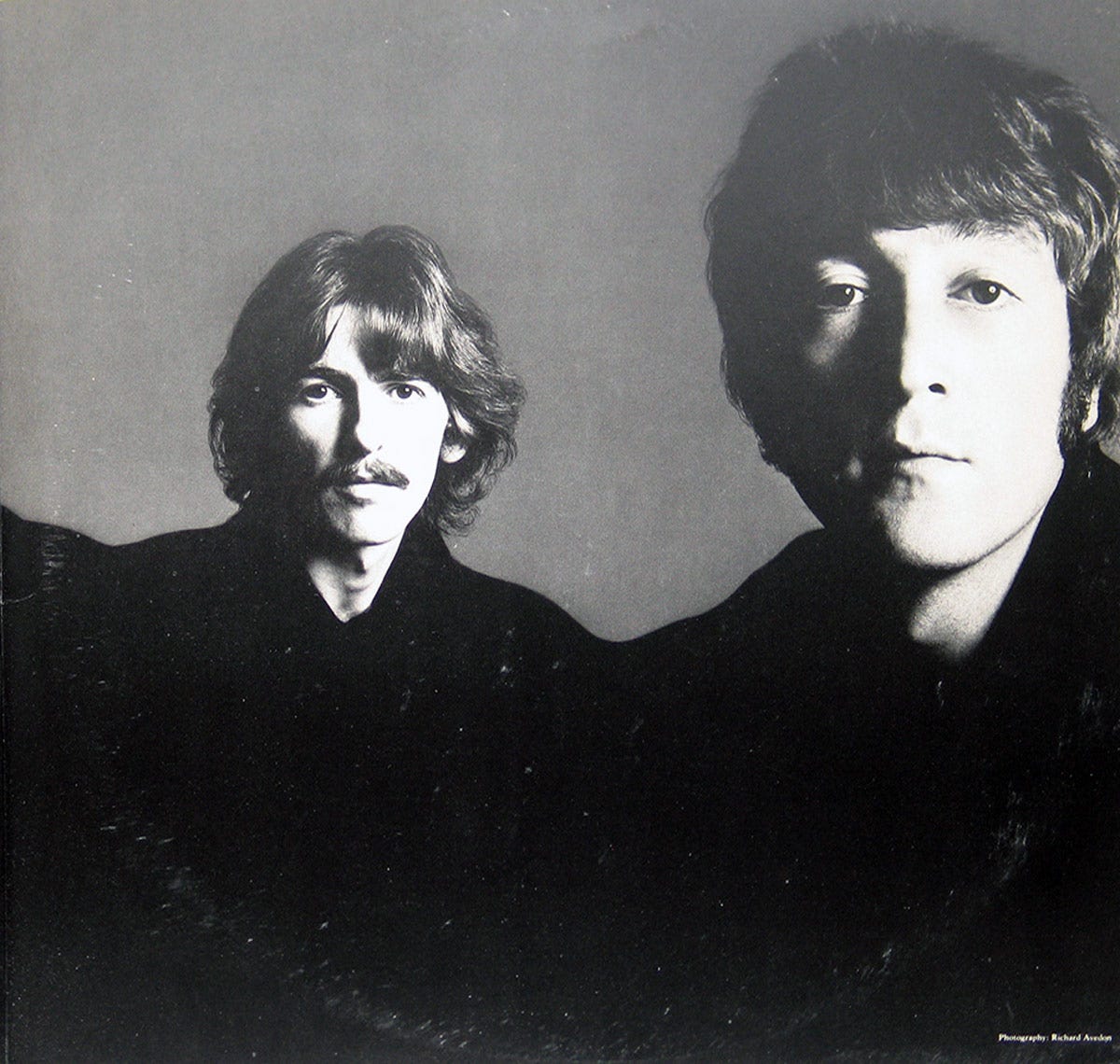

George Harrison and John Lennon, The Beatles - Love Songs (1977) - Vinyl LP Album Details & Collector’s Gallery via Creative Commons

Lennon portrait vector image via Public Domain / “Jenny Erpenbeck Frankfurt Book Fair 2018,” by Heike Huslage-Koch via Creative Commons

I loved the 1996 mix of Real Love, and was disappointed by the new mix. By “cleaning up” Lennon’s vocal, you lose something. I did love the 2025 FAAB mix.

Beautiful

Please take a look at mine on Lennon and strawberry fields forever

https://substack.com/@collapseofthewavefunction/note/p-181780578?r=5tpv59&utm_medium=ios&utm_source=notes-share-action