-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 26.3k

Description

With @pritamdamania87 @gqchen @aazzolini @satgera @xush6528 @zhaojuanmao

Master Design Doc:

- Distributed Model Parallel Design: [RFC] RPC Based Distributed Model Parallel #23110

Background

RRef stands for Remote REFerence. Each RRef is owned by a single worker

(i.e., owner) and can be used by multiple users. The owner stores the real

data referenced by its RRefs. RRef needs to support fast and scalable RPC.

Hence, in the design, we avoid using a single global master to keep RRef states,

instead owners will keep track of the global reference counts

for its RRefs. Every RRef can be uniquely identified by a global RRefId,

which is assigned at the time it is first created either on a user or on the

owner.

On the owner worker, there is only one OwnerRRef instance, which contains the

real data, while on user workers, there can be as many UserRRefs as necessary,

and UserRRef does not hold the data. All usage on the OwnerRRef should

retrieve the unique OwnerRRef instance using the globally unique RRefId.

A UserRRef will be created when it is used as an

argument or return value in dist.rpc or dist.remote call, but RRef forking

and reference counting (RC) are completely transparent to applications. Every

UserRRef will also have its globally unique ForkId.

Assumptions

Transient Network Failures

The RRef design aims to handle transient network failures by retrying messages.

Node crashes or permanent network partition is beyond the scope. When those

incidents occur, the application may take down all workers, revert to the

previous checkpoint, and resume training.

Non-idempotent UDFs

We assume UDFs are not idempotent and therefore cannot be retried. However,

internal RRef control messages will be made idempotent and retryable.

Out of Order Message Delivery

We do not assume message delivery order between any pair of nodes, because both

sender and receiver are using multiple threads. There is no guarantee on which

message will be processed first.

RRef Lifetime

The goal of the protocol is to delete an OwnerRRef at an appropriate time. The

right time to delete an OwnerRRef is when there are no living UserRRefs and

Python GC also agrees to delete the OwnerRRef instance on the owner. The tricky

part is to determine if there are any living UserRRefs.

A user can get a UserRRef in three situations:

- (1). Receiving a UserRRef from the owner.

- (2). Receiving a UserRRef from another user.

- (3). Creating a new UserRRef owned by another worker.

(1) is the simplest case where the owner initiates the fork, and hence it can

easily increment local RC. The only requirement is that any UserRRef must

notify the owner before destruction. Hence, we need the first guarantee:

G1. The owner will be notified when any UserRRef is deleted.

As messages might come delayed or out-of-order, we need more

one guarantee to make sure the delete message is not sent out too soon. Let us

first introduce a new concept. If A sends an RPC to B that involves an RRef, we

call the RRef on A the parent RRef and the RRef on B the child RRef.

G2. Parent RRef cannot be deleted until the child RRef is confirmed by the owner.

Under (1), where the caller is UserRRef and callee is OwnerRRef, it simply

means that the user will not send out the delete message until all previous

messages are ACKed. Note that ACKed does not mean the owner finishes executing

the function, instead, it only means the owner has retrieved its local

OwnerRRef and about to pass it to the function, which is sufficient to keep

the OwnerRRef alive even if the delete message from the user arrives at the

owner before the function finishes execution.

With (2) and (3), it is possible that the owner only partially knows the RRef

fork graph or not even knowing it at all. For example, the RRef could be

constructed on a user, and before the owner receives the RPC call, the

creator user might have already shared the RRef with other users, and those

users could further share the RRef. One invariant is that the fork graph of

any RRef is always a tree rooted at the owner, because forking an RRef always

creates a new RRef instance, and hence every RRef has a single parent. One

nasty detail is that when an RRef is created on a user, technically the owner

is not its parent but we still consider it that way and it does not break the

argument below.

The owner's view on any node (fork) in the tree has three stages:

1) unknown → 2) known → 3) deleted.

The owner's view on the entire tree keeps changing. The owner deletes its

OwnerRRef instance when it thinks there are no living UserRRefs, i.e., when

OwnerRRef is deleted, all UserRRefs could be either indeed deleted or

unknown. The dangerous case is when some forks are unknown and others are

deleted.

G2 trivially guarantees that no parent UserRRef Y can be deleted before the

owner knows all of Y's children UserRRefs.

However, it is possible that the child UserRRef Z may be deleted before the

owner knows its parent Y. More specifically, this can happen when all of Z's

messages are processed by the owner before all messages from Y, including the

delete message. Nevertheless, this does not cause any problem. Because, at least

one of Y's ancestor will be alive, and it will

prevent the owner from deleting the OwnerRRef. Consider the following example:

OwnerRRef -> A -> Y -> Z

OwnerRRef forks to A, then A forks to Y, and Y forks to Z. Z

can be deleted without OwnerRRef knowing Y. However, the OwnerRRef

will at least know A, as the owner directly forks the RRef to A. A won't die

before the owner knows Y.

Things get a little trickier if the RRef is created on a user:

OwnerRRef

^

|

A -> Y -> Z

If Z calls to_here on the UserRRef, the owner at least knows A when Z is

deleted, because otherwise to_here wouldn't finish. If Z does not call

to_here, it is possible that the owner receives all messages from Z before

any message from A and Y. In this case, as the real data of the OwnerRRef has

not been created yet, there is nothing to be deleted either. It is the same as Z

does not exist at all Hence, it's still OK.

Protocol Scenarios

Let's now discuss how above two guarantees translate to the protocol.

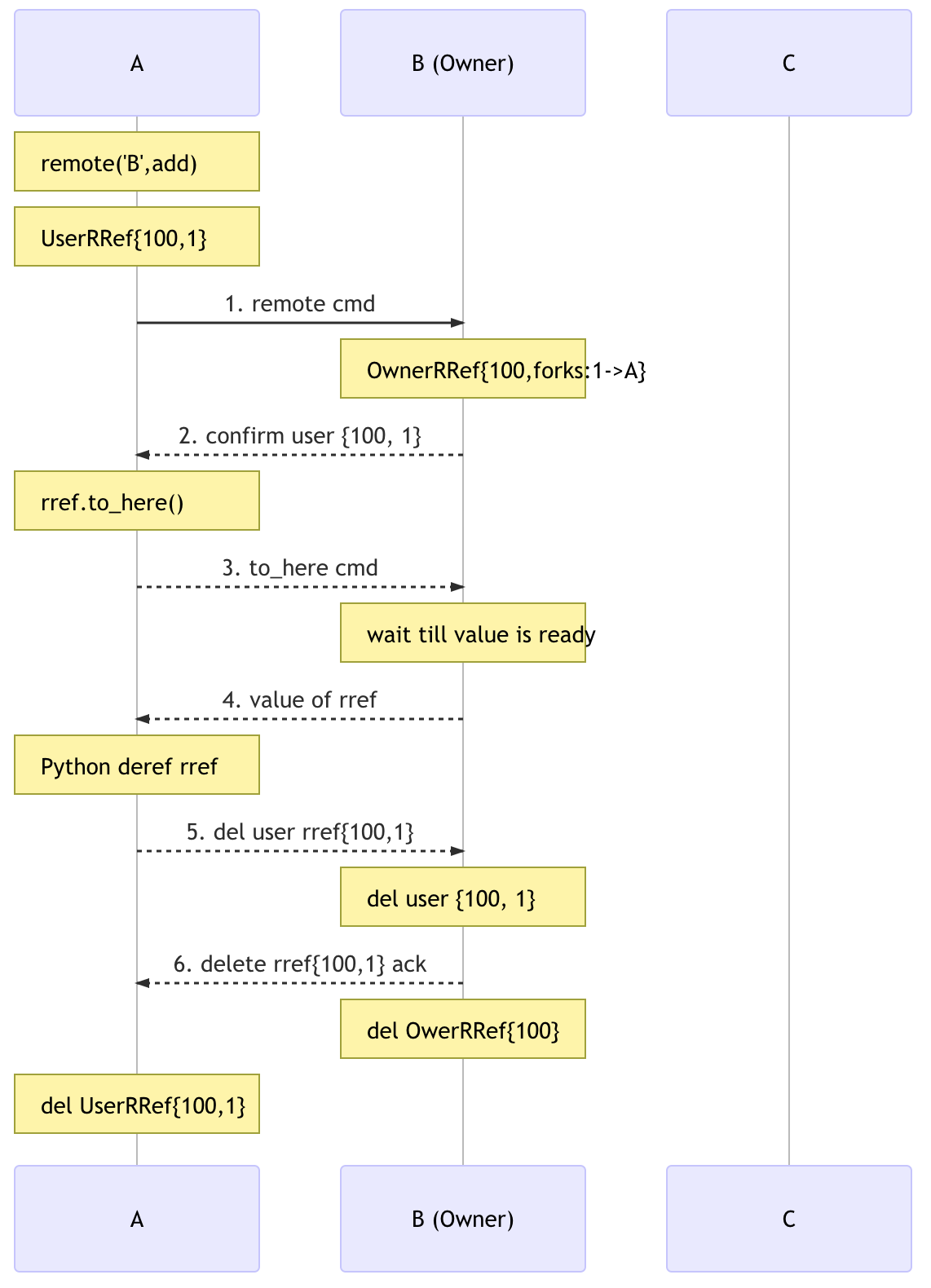

User to Owner RRef as Return Value

import torch

import torch.distributed.rpc as rpc

# on worker A

rref = rpc.remote('B', torch.add, args=(torch.ones(2), 1))

# say the rref has RRefId 100 and ForkId 1

rref.to_here()In this case, the UserRRef is created on the user A, then it is passed to the

owner B together with the remote message, and then the owner creates the

OwnerRRef. The method dist.remote returns immediately, meaning that the

UserRRef can be forked/used before the owner knows about it.

On the owner, when receiving the dist.remote call, it will create the

OwnerRRef, and immediately returns an ACK to acknowledge {100, 1}. Only

after receiving this ACK, can A deletes it's UserRRef. This involves both

G1 and G2. G1 is obvious. For G2, the OwnerRRef is a child

of the UserRRef, and the UserRRef is not deleted until it receives the ACK

from the owner.

The diagram above shows the message flow. Note that the first two messages from

A to B (remote and to_here) may arrive at B in any order, but the final

delete message will only be sent out when: 1) B acknowledges user RRef

{100, 1} (G2), and 2) Python GC agrees to delete the local UserRRef

instance.

User to Owner RRef as Argument

import torch

import torch.distributed.rpc as rpc

# on worker A and worker B

def func(rref):

pass

# on worker A

rref = rpc.remote('B', torch.add, args=(torch.ones(2), 1))

# say the rref has RRefId 100 and ForkId 1

rpc.rpc_async('B', func, args=(rref, ))In this case, after creating the UserRRef on A, A uses it as an argument in a

followup RPC call to B. A will keep UserRRef {100, 1} alive until it receives

the acknowledge from B (G2, not the return value of the RPC call).

This is necessary because A should not send out the delete message until all

previous rpc/remote calls are received, otherwise, the OwnerRRef could be

deleted before usage as we do not guarantee message delivery order. This is done

by creating a child ForkId of rref, holding them in a map until receives the

owner confirms the child ForkId. The figure below shows the message flow.

Note that the UserRRef could be deleted on B before func finishes or even

starts. However this is OK, as at the time B sends out ACK for the child

ForkId, it already acquired the OwnerRRef instance, which would prevent it

been deleted too soon.

Owner to User

Owner to user is the simplest case, where the owner can update reference

counting locally, and does not need any additional control message to notify

others. Regarding G2, it is same as the parent receives the ACK from the

owner immediately, as the parent is the owner.

import torch

import torch.distributed.rpc as RRef, rpc

# on worker B and worker C

def func(rref):

pass

# on worker B, creating a local RRef

rref = RRef("data")

# say the rref has RRefId 100

dist.rpc_async('C', func, args=(rref, ))The figure above shows the message flow. Note that when the OwnerRRef exits

scope after the rpc_async call, it will not be deleted, because internally

there is a map to hold it alive if there is any known forks, in which case is

UserRRef {100, 2}. (G2)

User to User

This is the most complicated case where caller user (parent UserRRef), callee

user (child UserRRef), and the owner all need to get involved.

import torch

import torch.distributed.rpc as rpc

# on worker A and worker C

def func(rref):

pass

# on worker A

rref = rpc.remote('B', torch.add, args=(torch.ones(2), 1))

# say the rref has RRefId 100 and ForkId 1

rpc.rpc_async('C', func, args=(rref, ))In order to guarantee that the OwnerRRef is not deleted before the callee user

uses it, the caller user holds its own UserRRef until it receives the ACK from

the callee user to confirm the child UserRRef, and the callee user will not

send out that ACK until the owner confirms its UserRRef (G2). The figure

below shows the message flow.

When C receives the child UserRRef from A, it sends out a fork request to

the owner B. Later, when the B confirms the UserRRef on C, C will perform two

actions in parallel: 1) send out the child ACK to A and 2) run the UDF.

cc @pietern @mrshenli @pritamdamania87 @zhaojuanmao @satgera @rohan-varma @gqchen @aazzolini