On February 13, World Radio Day acknowledges the importance of radio around the globe. The annual event has been taking place for a little over a decade, dating back to a 2011 proclamation by UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Member States and adoption by the United Nations General Assembly in 2012. The theme for World Radio Day 2026 is “radio and artificial intelligence.” UNESCO encourages radio stations to participate in the day and offers suggestions that align with the theme. One of the highlighted topic areas is memory and AI.

“Radio stations have thousands of hours of archives, often underutilized because they are difficult to index, browse or restore. AI can transform this dormant memory into an active resource, harnessing transcription, keyword searching, automatic summary and thematic upgrading. When direct reporting is impossible, coverage can be enhanced by historical archives.” – UNESCO

The Internet Archive’s Digital Library of Amateur Radio and Communications (DLARC) serves as this type of active resource, allowing visitors to dig into radio history. In recognition of World Radio Day and the second anniversary of the launch of the college radio sub-collection within DLARC, here are some recent additions and highlights from the DLARC college radio and community radio collections.

Radio Station Playlists

For much of college radio’s existence, the record of what was played was logged on paper playlists. Handwritten DJ playlists don’t always get saved, with station summaries of airplay or featured music more commonly found. These tops lists, radio surveys, adds lists, and airplay reports are compiled by radio stations and sent to record labels, musicians, trade publications, local newspapers, and zines. Results of the combined reports can be found in charts and lists published in CMJ New Music Report, Gavin Report, Rockpool, and similar publications.

DLARC College Radio recently received a large collection of digitized paper radio station playlists from the band Get Smart! Band members meticulously saved communication from college, community, high school and public radio stations that played their records in the 1980s. Representing stations from all over the United States and Canada, the playlists in this collection are mainly monthly summaries of the albums and artists that a radio station was playing. Sometimes they include commentary from station music directors or handwritten notes to the band. One thing that I love about these lists is that they are often printed on colorful paper, from a very 1985-feeling hot pink WHRB list from Harvard to an autumnal orange list from high school station KRVM-FM.

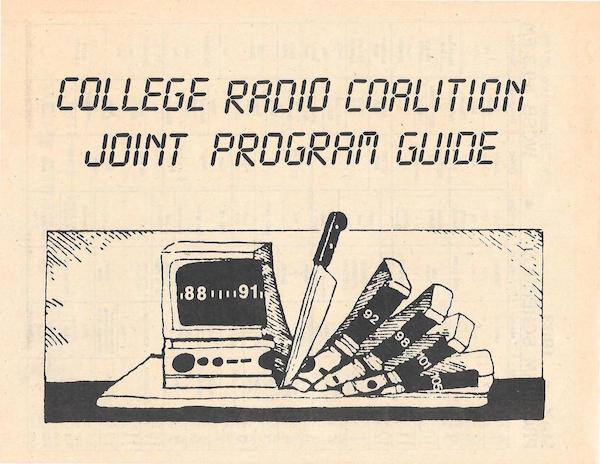

Additionally, a representative of the now-defunct Cleveland College Radio Coalition donated a collection of digitized copies of playlists, program guides and more. The group was formed in 1982 in order to help increase awareness for the college radio stations in Cleveland, Ohio and also produced a joint program guide.

Other newly added playlists include a batch from Bowling Green State University’s college radio station WBGU-FM in Bowling Green, Ohio. They form the bulk of a new WBGU-FM collection, which currently features flyers, program guides, correspondence, and training materials from 1995-1997.

You can peruse the entire collection of college radio playlists in DLARC College Radio.

Radio Station Stickers

Other new additions to DLARC College Radio include promotional stickers produced by college radio stations.

KVRX-FM collection from UT Austin

One of DLARC College Radio’s newest collections is from KVRX-FM, the student-run college radio station at University of Texas, Austin. The Internet Archive digitized a wide variety of KVRX materials, including ‘zines, DJ notebooks, record reviews, organization documents, posters, and newsletters, spanning the years 1986 to 2025.

Audio Transcriptions

Finally, in keeping with this year’s World Radio Day theme related to AI, the college radio collection has been enhanced by an AI-generated transcription tool within the media player of select audio items. This means that not only can one listen to recordings from college radio stations, but one can also read transcripts from radio shows, interviews, oral histories, and more. Audio with AI-generated transcripts in the DLARC College Radio collection includes:

- 1981 WUSB Ramones interview from 1981 (SUNY Stonybrook)

- 1955 WHRC interview with William F. Buckley, Jr. (Haverford College)

- WKDU oral histories (Drexel University)

- CKUT oral history Interviews (McGill University)

The Digital Library of Amateur Radio & Communications is funded by a grant from Amateur Radio Digital Communications (ARDC) to create a free digital library for the radio community, researchers, educators, and students. DLARC invites radio clubs, radio stations, archives and individuals to submit material in any format. To contribute or ask questions about the project, contact: Kay Savetz at [email protected]. Questions about the college radio sub-collection can be directed to Jennifer Waits at [email protected].